Back to Kinzler’s Global News Blog

The Economist, 2 juin

Hitting back : An astonishing raid deep inside Russia rewrites the rules of war

Ukraine’s high-risk strikes damage over 40 top-secret strategic bombers

Full text :

SHORTLY AFTER noon on June 1st, Russian social media began flashing, alerting the world to Ukraine’s most audacious operation on Russian territory to date. In Irkutsk province in eastern Siberia, some 4,000km from Ukraine, locals posted footage of small quadcopter drones emerging from lorries and flying toward a nearby airfield, home to some of Russia’s most important strategic bombers. “I work at a tire shop,” one wrote. “A truck pulled in, and drones flew out of it.” From an airbase near Murmansk, in Russia’s far north, came similar stories: “The driver’s running around…drones are flying from his truck toward the base.” Other alarmed posts soon followed from airbases in Ryazan and Ivanovo provinces, deep in central Russia.

Ukraine’s main security agency, the SBU, has since claimed responsibility for the operation, which it has codenamed “Spider Web”. It said at least 41 Russian aircraft were destroyed or damaged across four airfields, including rare and extremely expensive A-50 early-warning planes (Russia’s equivalent of the AWACS) and Tu-22M3 and Tu-95 strategic bombers. The agency also released footage in which its pugnacious chief, Vasily Maliuk, is heard commenting on the operation. “Russian strategic bombers,” he says in his recognisable growl, “all burning delightfully.”

The strike is one of the heaviest blows that Ukraine has landed on Russia in a war now well into its fourth year. Russia has relatively small numbers of strategic bombers—probably fewer than 90 operational Tu-22, Tu-95 and newer Tu-160s in total. The planes can carry nuclear weapons but have been used to fire conventional cruise missiles against Ukrainian targets, as recently as last week. That has made them high-priority targets for Ukrainian military planners. Many of the aircraft are old and no longer produced—the last Tu-22M3s and Tu-95s were made more than 30 years ago—and their replacements, the Tu-160, are being manufactured at a glacial pace.

The fact that Ukraine was able to damage or destroy such a large number of Russia’s most advanced aircraft deep inside the country reflects the development of its deep-strike programme, as well as the remarkable extent to which Ukraine’s undercover operatives are now able to work inside Russia. Since the start of the Kremlin’s all-out invasion, Ukraine’s operations have expanded in range, ambition and sophistication. Western countries have provided some assistance to Ukraine’s deep-strike programme—on May 28th Germany promised to finance Ukrainian long-range drones—but much of the technology and mission planning is indigenous.

Today’s operation is likely to be ranked among the most important raiding actions in modern warfare. According to sources, the mission was 18 months in the making. Russia had been expecting attacks by larger fixed-wing drones at night and closer to the border with Ukraine. The Ukrainians reversed all three variables, launching small drones during the day, and doing so far from the front lines. Ukraine had launched drones from within Russia previously; the difference was the scale and combined nature of the operations.

Commentators close to the Ukrainian security services suggest that as many as 150 drones and 300 bombs had been smuggled into Russia for the operations. The quadcopters were apparently built into wooden cabins, loaded onto lorries and then released after the roofs of the cabins were remotely retracted. The drones used Russian mobile-telephone networks to relay their footage back to Ukraine, much of which was released by the gleeful Ukrainians. They also used elements of automated targeting, the accounts claim.

A Ukrainian intelligence source said it was unlikely that the drivers of the trucks knew what they were carrying. He compared this aspect of the operation to the 2022 attack on Kerch bridge, where a bomb concealed in a lorry destroyed part of the bridge linking Crimea with the mainland. “These kinds of operations are very complex, with key players necessarily kept in the dark,” he said. The source described the operation as a multi-stage chess move, with the Russians first encouraged to move more of their planes to particular bases by Ukrainian strikes on other ones. Three days before the attack, dozens of planes had moved to the Olenya airfield in Murmansk province, according to reports published at the time. It was precisely here that the most damage was done.

The operation casts a shadow over a new round of peace talks that is scheduled to start in Istanbul on June 2nd. Ukraine has been terrorised in recent months by Russia’s own massive strikes, sometimes involving hundreds of drones: one that took place overnight beginning on May 31st apparently involved a record 472 drones, the Ukrainian authorities say. Kyiv had been looking for ways to demonstrate to Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president, that there is a cost to continuing the war. But the question is whether this operation has moved the dial, or simply raised the stakes. Chatter on Russian patriotic social-media networks has called for a severe response, likening the moment to Pearl Harbour, Japan’s attack on America’s Pacific Fleet in 1941. A senior Ukrainian official acknowledged that the operation carried risks of turning Western partners away from Ukraine. “The worry is that this is Sinop,” he said, referring to Russia’s strike on an Ottoman port in 1853 that ended up isolating the attacker on the world stage.

Western armed forces are watching closely. For many years they have concentrated their own aircraft at an ever smaller number of air bases, to save money, and have failed to invest in hardened hangars or shelters that could protect against drones and missiles. America’s own strategic bombers are visible in public satellite imagery, sitting in the open. “Imagine, on game-day,” writes Tom Shugart of CNAS, a think-tank in Washington, “containers at railyards, on Chinese-owned container ships in port or offshore, on trucks parked at random properties…spewing forth thousands of drones that sally forth and at least mission-kill the crown jewels of the [US Air Force].” That, he warns, would be “entirely feasible”. ■

The Wall Street Journal, 2 juin

Ukraine Still Isn’t Defeated

Daring drone raids on air bases deep inside Russia show Kyiv’s continuing will to fight.

Full text :

JD Vance likes to say that Ukraine isn’t winning its war with Russia, which the Vice President seems to think is an argument for withdrawing U.S. military support. But if the will to fight is worth something, then Ukraine is still showing its mettle as it tries to repel the Kremlin’s designs for conquest.

Ukraine’s daring weekend drone attack on military bases deep inside Russia is a brilliant example of creativity and resolve. Ukraine sources say it was able to smuggle drones across Russia, fire them at close proximity to air bases, and destroy numerous aircraft. The planes reportedly included bombers that fire cruise missiles at Ukraine and some that can carry nuclear payloads.

It isn’t clear how many planes were destroyed, but there was enough damage that Russia’s defense ministry felt obliged to acknowledge the strikes. Bases were hit in Siberia and in the far Russian east.

The drone raids won’t alter the course of the war, but they show the ability of Ukraine to strike far from its border with Russia. The intelligence required to pull off the operation, supposedly in the planning for 18 months, is also reason for the Kremlin to be discomfited. Did Ukraine have some Russian help?

Ukraine suffered a setback on Sunday when a Russian missile attack on a military training site killed a dozen people and wounded many more. Russia still has the advantage in firepower, especially in missiles that need to be intercepted with Ukraine’s dwindling supply of air-defense interceptors. The Trump Administration says it wants to stop the killing, but the best way to do that is to supply more air defenses to Kyiv.

Ukraine says it is sending a delegation to Turkey on Monday for what is supposed to be the next round of peace talks with Russia. But it doesn’t appear that Russia is willing to put any serious proposal on the table, a continuing insult to President Trump’s demands for a cease-fire.

It’s time for Sens. Lindsey Graham and Richard Blumenthal to move their bill sanctioning countries that buy oil and gas from Russia. Republicans want to defer to Mr. Trump, but Senators aren’t potted plants. Sooner rather than later, they need to show they mean what they say about helping a desperate ally fight for its freedom against a marauding dictator who won’t stop if he succeeds in Ukraine.

The Wall Street Journal, 28 mai

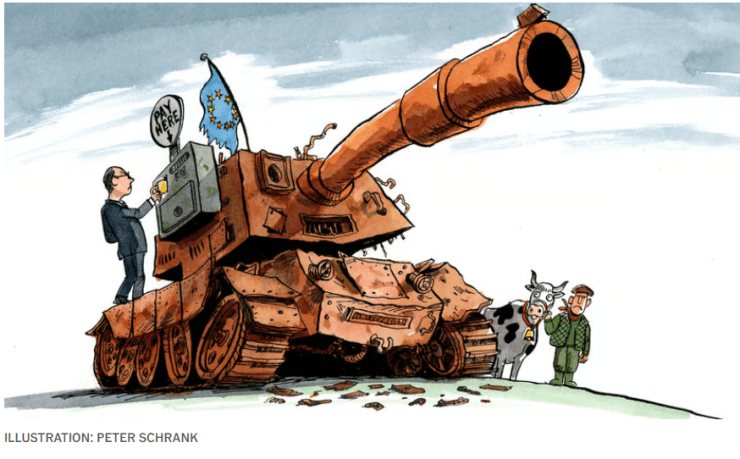

Putin Has Retooled Russia’s Economy to Focus Only on War

Moscow has expanded military recruitment and boosted weapons production. Peace could jeopardize the economic gains.

Full text :

Russia’s successes on the front lines in Ukraine are a big reason why Vladimir Putin isn’t yet ready to sign up to President Trump’s peace efforts. Some of his neighbors fear the success of the war machine now driving its economy means he never will.

In the early stages of the war, the Russian president put the country on a footing for a long conflict. Putin retooled the economy to churn out record numbers of tanks and howitzers, while using sizable signing bonuses of up to a year’s salary to raise a massive army. At one point, more than a thousand recruits were signing up each day to fight.

This increase saved Moscow from the initial losses it suffered after failing to quickly capture Kyiv three years ago. Now it is helping Russian forces advance westward again, taking more than 100 square miles in the past month. The gains have given Putin the latitude to slow walk peace negotiations and shrug off direct talks with his Ukrainian counterpart, Volodymyr Zelensky, despite growing European pressure and Trump’s own exasperation with the lack of progress in ending the war.

But if or when Putin is ready to make peace, unwinding his military buildup could prove a trickier task.

“It is absolutely imperative for Russia to continue to rely on the military industry, because it [has] become the driver of economic growth,” said Alexander Kolyandr, a senior fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis. “For a while, it will be next to impossible for Russia to reduce military spending.”

Russia’s arms industry has enjoyed billions of dollars in stimulus in recent years to boost production lines and keep them running at breakneck speed 24 hours a day. The influx of cash has boosted wages—partly to compete with military payouts—and fueled rising living standards for thousands of Russians in the country’s poorer backwaters.

President Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin spoke for more than two hours but failed to agree on an immediate cease-fire in Ukraine. WSJ National Security Reporter Alexander Ward unpacks the call. Photo Illustration: Reuters/Associated Press

“I’m not sure that Vladimir Putin himself has a strategy for how to unwind the war,” said Vice President JD Vance after his meeting with Pope Leo XIV, speculating with reporters as to why Putin hasn’t bitten on Trump’s efforts to cease hostilities.

Trump has grown increasingly willing to criticize Putin for his refusal to end hostilities. Over the weekend he said in a social-media post that the Russian leader had gone crazy and told reporters “he’s killing a lot of people; I’m not happy about that.” On Tuesday Trump expressed his frustration in another post.

“What Vladimir Putin doesn’t realize is that if it weren’t for me, lots of really bad things would have already happened to Russia, and I mean REALLY BAD. He’s playing with fire!” Trump wrote.

If the war does end in Ukraine, some of Russia’s neighbors worry its war economy might be refocused on them.

In the Baltics, Estonian military planners grimly discuss the possibility of war spilling into NATO territory. In Kazakhstan, analysts carefully watch for signals that Russia could make a move into the north of the country, where a large ethnic Russian population still lives.

These fears stem partly from the belief that the Kremlin would rather keep the tens of thousands soldiers fighting on some other front line rather than bring battle-hardened and often traumatized men back home. After the end of World War II, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin viewed returning veterans as a threat and sent many to the gulags to rid himself of the domestic pressures they could cause.

Today, peace would likely see many of the hundreds of thousands of troops in Ukraine, particularly those who signed short-term contracts, demobilized and sent back to civilian life at a time of slowing economic and wage growth.

“It’s not going to be a good idea to cut those wages radically or in a very short time,” said Volodymyr Ishchenko, of the Free University of Berlin. “It’s not a good idea for the state to disappoint armed men.”

If the fighting in Ukraine ends, Russia’s military will still need men. The arms industry will still be building the guns and vehicles needed to replace the Soviet stockpiles lost on the front line, but at a slower pace than during the war. Job losses on factory lines, together with an increasingly stagnating economy, could stir some discontent among those who saw the war bring the biggest redistribution of wealth since the fall of the Soviet Union.

“Without an existential crisis like the war in Ukraine, it would be hard to justify continuing to pour money into the defense industry at the rate we already are,” said Ruslan Pukhov, head of the Moscow-based Center for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies. “And Putin—even if they say he is an evil totalitarian—he is very sensitive about what people think and what they want.”

Already there are signs that the boost from the war and a surge in wages and living standards is beginning to level out. The declining price of oil adds another note of uncertainty for the future.

Some arms industries are exploring the idea of trying to export their extra production and return to Russia’s heyday as the second-largest arms exporter in the world, a position it held before the start of the war. But analysts say that is unlikely with an industry that has already lost market share in Asia and Africa, has a host of customers who depend on Russia for credit to buy the weapons and has given priority to quantity over quality.

In some ways, Russia finds itself in a situation similar to the U.S. after World War II or Nazi Germany before the war—when their arms industries were the drivers of growth. But unlike the U.S., where military advances have spilled into the civilian sector—such as the mass production of penicillin or the internet—Russia’s defense industry is unlikely to produce technological breakthroughs to drive sustained growth.

Instead, while the civilian economy is suffering from a lack of manpower, causing price increases in eggs and potatoes, some see the shrinking of the arms industry as inevitable. The way that slowdown is managed will be crucial.

“When you reduce fiscal stimuli, you have to be very careful…there are so many people who are interested in keeping this merry-go-round going,” said Kolyandr.

https://www.wsj.com/world/russia/russia-putin-ukraine-war-economy-7e410058?mod=hp_lead_pos2

Le Figaro, 27 mai

Guerre en Ukraine : Friedrich Merz ouvre un nouveau chapitre du soutien militaire européen à Kiev

DÉCRYPTAGE – Cette déclaration du chancelier allemand participe de la nouvelle stratégie de communication occidentale dirigée contre Moscou privilégiant «l’ambiguïté stratégique».

Full text :

Les alliés occidentaux ne fixent plus de «limitations» à la portée des armes qu’ils envoient à l’Ukraine : par cette déclaration, le chancelier Friedrich Merz ouvre un nouveau chapitre du soutien militaire européen à Kiev, et ceci au moment où la position de Washington à l’égard du conflit reste des plus nébuleuses et où la Russie intensifie ses attaques nocturnes sur le territoire de son voisin. « Cela signifie que l’Ukraine peut désormais se défendre, par exemple en attaquant des positions militaires en Russie (…) ce qu’elle ne faisait pas il y a quelque temps, à quelques exceptions près. Elle peut le faire maintenant », a déclaré lundi 26 mai le dirigeant allemand lors d’un entretien à la télévision publique WDR.

Ces propos ont aussitôt déclenché la colère de Moscou. « Si ces décisions ont vraiment eu lieu, elles vont absolument à l’encontre de nos aspirations à entrer dans un règlement politique. Il s’agit donc d’une décision assez dangereuse », a déclaré Dmitri Peskov, le porte-parole du Kremlin dans une vidéo diffusée par des médias russes.

Côté allemand, cette déclaration semble participer d’une nouvelle stratégie de communication édictée il y a peu à Berlin à l’encontre de Moscou, et selon laquelle le secret relatif doit primer en matière de livraison d’armes. Il s’agit d’un « souhait du chancelier fédéral de réduire la communication sur les systèmes d’armes individuels », avait déclaré il y a deux semaines le porte-parole du gouvernement, Stefan Kornelius. « Les systèmes » en question sont les missiles de croisière Taurus, que le précédent chancelier Olaf Scholz, pour diverses raisons, n’a jamais souhaité livrer. L’ex dirigeant SPD arguait tour à tour des risques d’escalade du conflit, de perte de contrôle dans le commandement de la mise à feu, ou d’autres motifs opérationnels.

Stratégie partagée à Paris

Ces missiles sont dotés d’une portée atteignant 500 kilomètres, supérieure à celle des missiles Scalp français ou Storm Shadow britanniques (plus de 250 kilomètres), déjà présents en Ukraine, tout comme les Atacms américains. Depuis des mois, Friedrich Merz qui avait toujours critiqué dans l’opposition la timidité d’Olaf Scholz, se montre ouvert à cette livraison tout en l’assortissant de multiples conditions faisant douter de la sincérité de son engagement. Pour sa part, le ministre de la Défense SPD Boris Pistorius semblait freiner ces initiatives, estimant que cette question des Taurus revêtait un aspect secondaire.

Cette ambiguïté stratégique telle que théorisée par Berlin, est également partagée à Paris. « Nous ferons preuve de transparence envers les Ukrainiens, nous répondrons à leurs besoins, mais nous en parlerons le moins possible, car il est également dans leur intérêt que nous ne nous exprimions pas trop à ce sujet », avait déclaré Emmanuel Macron en recevant son homologue allemand début mai. L’opposition au Bundestag, notamment les Verts, critique ce manque de transparence mais les principaux intéressés, à l’inverse, s’en félicitent.

«Je suis au courant de ces secrets », expliquait l’ambassadeur ukrainien à Berlin, Oleksii Makeiev, au lendemain de la visite conjointe du quatuor européen à Kiev (Merz, Starmer, Tusk, Macron). Et le diplomate d’ajouter : «l’Allemagne tiendra ses promesses. Et nous savons exactement quoi et quand. Et nous sommes satisfaits ».

The Wall Street Journal, 26 mai

Trump Calls Putin ‘Crazy’ After Massive Russian Aerial Assaults on Ukraine

At least 12 killed and dozens injured as strikes across the country hit residential buildings, Ukrainian officials say

Full text :

President Trump issued a strong rebuke of Russian President Vladimir Putin after Moscow stepped up missile-and-drone assaults on the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv and other regions in attacks that killed at least 12 people.

Russia struck with a total of 367 drones and missiles—one of the largest single-night raids of the war, according to the Ukrainian Air Force—in a second consecutive day of pounding attacks that sent civilians running for shelters in the middle of the night. Officials said that children were among those killed and that a further 60 were injured and more than 80 residential buildings damaged across the country, even as more than 300 of the missiles and drones were shot down.

President Volodymyr Zelensky called for more economic sanctions against Russia to force it to stop its invasion, which Russian President Vladimir Putin has refused to do despite Trump’s entreaties.

“Russia is dragging out this war and is continuing to kill on a daily basis,” he said on social media. “It can’t be ignored. The silence of America, the silence of others in the world, only encourages Putin.”

Trump late Sunday criticized Putin, saying in a social-media post, “He has gone absolutely CRAZY! He is needlessly killing a lot of people, and I’m not just talking about soldiers. Missiles and drones are being shot into Cities in Ukraine, for no reason whatsoever.” Trump was also critical of Zelensky, saying in the same post that Zelensky “is doing his Country no favors by talking the way he does.”

The Russian Defense Ministry said its strikes had targeted Ukrainian military-production facilities. The ministry said it had downed 110 Ukrainian attack drones in regions across the west of Russia, including Moscow. Ukrainian officials said that their large-scale drone attacks on Russian targets in recent days have damaged several Russian military-industrial facilities, including a factory that makes parts for ballistic missiles.

The increased ferocity of Russia’s assaults comes days after Trump demurred on threats to sanction Russia further if it didn’t sign an immediate, 30-day cease-fire. In a two-hour call with Trump last week, Putin refused a truce that Kyiv consented to in March. Trump has publicly insisted that Putin wants peace, but in a call with European leaders this week, conceded that Putin isn’t ready for peace, The Wall Street Journal reported, because he believes he is winning.

Zelensky said only pressure on the Kremlin would yield results.

“Resolve is important right now—the resolve of the United States, the resolve of European countries, of all those in the world that want peace,” Zelensky said Sunday. “The world knows all the weak points of the Russian economy. It is possible to stop the war, but only thanks to the necessary pressure on Russia.”

Ukraine countered the aerial assault with a combination of missile defense, Western-provided F-16 jet fighters and small drones used to intercept Russian strike drones, an Air Force spokesman said.

Trump last week said that Ukraine and Russia should continue negotiations over a peace deal among themselves—talks that so far have yielded only one tangible result: a three-day exchange of around 1,000 prisoners from each side that concluded Sunday.

Russia has confounded Trump’s efforts to end the war, which it launched in February 2022, insisting that its original war goals of a neutered Ukraine under firm Russian influence be met even as its army struggles to advance in its neighbor’s east.

The Economist, 26 mai

The war in the air : Russia is raining hellfire on Ukraine

New attacks push its air defences to saturation point

Full text :

AYEAR AGO, for 30 drones to strike Ukraine in a single night was considered exceptional. Now Russia is saturating Ukraine’s air defences with hundreds of them. On May 25th the Kremlin pummelled the country, with what it called a “massive strike” against Ukrainian cities, featuring 298 drones, probably a record. Russia is using more missiles, too: 69 were fired on the same night. As a result, Ukraine is once again stepping into the unknown. If the current ceasefire talks fail, which seems highly probable, air-defence units will need to ration their interceptors. More Russian missiles and drones will get through, to strike towns, cities and critical industry.

Russia’s air war stepped up at the start of the year (see chart), with a marked shift in the hardware it uses. Ballistic missiles, many supplied by North Korea, are now centre-stage; alongside a new, more lethal, generation of Shahed attack drones. The ballistic missiles are hard to stop because of their speed; only Ukraine’s dwindling stock of Patriot PAC-3 missiles offers any real chance of interception. Meanwhile, the Shaheds, now in their sixth modification since the first of them were shipped to Russia by Iran in 2023, are using machine-learning to strike well-protected targets like Kyiv. On May 24th drones took chunks out of buildings in the northern suburbs of the capital. Two weeks earlier, one drone equipped with a fuel-air warhead made a hole in a shopping centre just nearby, blowing out windows as much as 300m away. The same week, another, stuffed with delayed-action cluster munitions, hit a training range on the south-eastern edge of the city.

The main challenge facing Ukraine’s air-defence crews is the sheer number now flying at them. Last year the Kremlin was producing around 300 Shahed drones a month; the same number now rolls out in under three days. Ukrainian military intelligence says it has documents that suggest that Russia plans to increase its drone production to 500 a day, suggesting that attack swarms of 1,000 could become a reality. That is probably a stretch, cautions Kostiantyn Kryvolap, a Ukrainian aviation expert. Russia’s arms industry runs on bluster and false reporting, he says. “But it’s clear the numbers are going to increase significantly.” Even if Ukraine manages to stabilise the front lines in the east, the difficulties of protecting the skies will only grow.

In a skunkworks in a hidden corner of Kyiv, a ragtag group of engineers are pulling apart the innards of a Russian-made Shahed drone. Every piece of metal that falls on Ukrainian cities ends up in laboratories such as this for a complete post-mortem. The aim is to document the weapons’ tricks; to re-engineer anything that works, and send a version of it back from whence it came. In the past month, there has been no let-up in the work. Despite hopes of a ceasefire, Russia is finding more and more ways to cut through Ukraine’s air defences, which face mounting difficulties from a shortage of interceptor missiles, changing enemy tactics and unfriendly American politics.

As they continue to dissect the latest Shahed delivery, the engineers say one of their biggest worries is how the Russian drones are now being controlled. The newest models are unfazed by Ukraine’s electronic warfare, they say. This is because they no longer rely on jammable GPS, are driven by artificial intelligence, and piggyback on Ukraine’s own internet and mobile internet networks. The team say they recently discovered a note inside one of the drones they were dismantling—presumably left by a sympathetic Russian engineer—which hinted at the new control algorithm. The drones are controlled via bots on the Telegram social-media platform, the note indicated, sending flight data and live video feeds back to human operators in real time.

Not long ago, most of the drone-hunting was done by mobile crews with cheap machine guns, shoulder-fired missiles and short-range artillery. Now, says Colonel Denys Smazhny, an officer in the air-defence forces, the drones routinely manoeuvre around these groups. They initially fly low to avoid detection, then climb sharply to 2,000–2,500 metres as they near cities, breaching the threshold for small-calibre guns. So Ukraine is turning to helicopters, F-16 fighter jets and interceptor drones, which have begun to show good results. A senior official says the air defences around Kyiv are still knocking out around 95% of the drones that Russia throws at it. But the 5% that slip through cause serious damage.

Ukraine still has a fighting chance against drones and cruise missiles. But the outlook against ballistic threats is bleaker. Only a handful of countries have systems that can counter such fast and destructive weapons. In the Western world, the American Patriot system has an effective monopoly on the ballistic air-defence business. Ukraine now has at least eight Patriot batteries, though at any given time some are damaged and under repair.

Their crews operate them with impressive skill. Since spring 2023, they’ve knocked down more than 150 ballistic and air-launched ballistic missiles. But the systems have been largely concentrated around Kyiv. Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukraine’s president, says Ukraine needs at least ten more, with corresponding stockpiles of the PAC-3 interceptors the system uses, to start to make its cities feel secure. He insists the country is ready to pay whatever it takes, presumably using European money. The White House response has been non-committal.

The problem is that Ukraine has slipped from being a priority for the Biden administration to just one of only many potential customers competing for limited production under Donald Trump. Lockheed Martin, which builds the Patriot systems and their PAC-3s, is increasing its output to 650 missiles per year. But this is about 100 fewer than projected Russian production of ballistic missiles, with a Ukraine government source estimating the Kremlin has a 500-missile stockpile. It usually takes two PAC-3 interceptor missiles to intercept a Russian ballistic missile.

For China hawks in the Trump administration, a Patriot system or missile sent to Ukraine is one fewer that can be sent to the Pacific theatre. Even the most Ukraine-friendly administration—which this one is not—would find it hard to keep pace with the persistent Russian threat. Ukraine has asked for the right to produce its own version of the PAC-3 under licence, but knows that is unlikely. Production is due to begin in Germany, but only at the end of 2026. There are other joint-production projects in the pipeline too. But in all cases the breakthrough point is at least a year away.

Ukraine may have to develop a survival strategy that pairs air defence with air offence and deterrence. “We will have to destroy Russian launch complexes, the factories and the stores,” says Mr Kryvolap, the aviation expert. “We should be under no illusions.” ■

https://www.economist.com/europe/2025/05/25/russia-is-raining-hellfire-on-ukraine

L’Express, 25 mai

Vera Grantseva : “La stratégie de Poutine reste la guerre totale contre l’Europe”

Monde. Selon la politologue russe, le président américain est le meilleur allié du Kremlin dans sa guerre contre l’Ukraine.

Full text :

C’est une vieille méthode soviétique que Vladimir Poutine maîtrise à merveille : brandir l’étendard de la paix tout en faisant la guerre… Feindre l’envie de négocier tout en pilonnant l’Ukraine. Le mensonge pour seul horizon, une stratégie qu’un autre dirigeant du monde pratique sans limite : Donald Trump, adepte des réalités parallèles et des vérités alternatives. La paire s’est bien trouvée, et le Kremlin se joue à plein de la naïveté de Trump, estime Vera Grantseva, politologue russe exilée en France depuis 2020, enseignante à Sciences Po Paris. Entretien.

L’Express : Poutine continue de prétendre qu’il est prêt à “négocier” pour finir la guerre en Ukraine. Que cherche-t-il? A gagner du temps?

Vera Grantseva : Pour analyser la stratégie de Poutine, il faut garder deux paramètres en tête. D’abord, que la communication n’est pas pour lui un moyen d’expliquer ou de trouver une solution, mais une arme destinée à tromper. C’est ce qu’il a appris à l’école du KGB. Ensuite, que les paroles n’ont aucune valeur à ses yeux. Seuls les actes comptent – et c’est ce que les Occidentaux n’arrivent pas à comprendre, car ils vivent dans un autre monde. Quand vous écoutez Poutine, dites-vous bien que ses mots ne valent rien. Regardez ce qu’il fait, pas ce qu’il dit.

Analysons maintenant les velléités de Poutine de “négocier” à la lumière de ces deux règles. Pourquoi prétend-il vouloir des pourparlers? D’abord car la pression monte du côté des Etats-Unis et du Sud Global. Lors de sa visite à Moscou pour célébrer le “Jour de la Victoire” le 9 mai, Xi Jinping a appelé de ses voeux un “accord de paix juste, durable et contraignant, accepté par toutes les parties concernées”. Quelques jours plus tard, le président brésilien Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva lui a emboîté le pas, se disant prêt à convaincre Poutine de négocier. Du côté de Washington aussi, Donald Trump s’impatiente.

Vladimir Poutine voit dans le locataire de la Maison-Blanche une opportunité pour gagner cette guerre. Pour lui, Trump peut se comporter de deux façons, et les deux sont gagnantes. Premier scénario : Moscou arrive à rallier Trump à sa cause et ce dernier fera pression sur l’Ukraine et l’Europe pour céder les territoires occupés à la Russie. C’est une façon de remporter cette guerre par la voie politique car sur le terrain militaire, les troupes russes n’y arrivent pas. Deuxième scénario : les négociations échouent, douchant les espoirs de Donald Trump. Au lieu de réfléchir aux raisons de cet échec, il sera juste déçu et vexé et se retirera de ces négociations et de la gestion de cette guerre en général. Cette option est aussi favorable pour Poutine car le président russe pense qu’en se retirant de ces négociations, Trump arrêtera dans la foulée l’aide à l’Ukraine. Aujourd’hui, le soutien américain ne constitue que 20 % de l’aide internationale à Kiev, mais avec des éléments cruciaux pour le front, comme les systèmes de défense antiaérienne Patriot. Poutine est persuadé que sans l’aide américaine, l’Ukraine va s’effondrer sur le plan militaire et moral. Dans ce contexte, il a accepté l’idée de négocier – mais en aucun cas de faire un compromis. D’ailleurs on a vu lors de la rencontre des délégations russe et ukrainienne à Istanbul que les Russes sont restés sur les mêmes conditions maximalistes annoncées en 2022. Pire, ils ont fait monter les enchères en menaçant d’annexer d’autres régions ukrainiennes.

Quelle attitude adopter face au bluff permanent de Poutine?

Poutine ne comprend que la force, il n’a aucun respect pour l’idée même de compromis ou de négociation, il prend cela comme des signes de faiblesse. C’est pourquoi toutes les tentatives de leaders occidentaux, à la veille de la guerre – quand Emmanuel Macron et Olaf Scholz se sont rendus à Moscou – ont été contreproductives. Poutine les a interprétées comme un feu vert pour lancer sa guerre. Il y a vu la confirmation de sa vision de l’Europe : une Europe faible et incapable de lui résister. Comment utiliser la force face à Poutine? La voie la plus courte et efficace est la voie militaire. Si l’Otan s’était engagée dès le début dans cette guerre, elle aurait duré trois jours, car on a vu les faiblesses de l’armée russe. Mais cette option n’est pas acceptable pour l’Europe d’aujourd’hui, pour tout un tas de raisons, notamment le risque d’escalade nucléaire.

Que restait-il? La voie économique, avec les sanctions accompagnées de discours fermes avertissant la Russie que tant qu’elle continuera cette guerre, elle sera isolée sur la scène internationale. Cette voie est plus lente et ne donnera pas de résultats à court terme. A moyen terme, l’économie russe souffre et sur le long terme cela pourra avoir un effet. Si les sanctions étaient insignifiantes, le Kremlin ne chercherait pas à les faire lever… Mais il n’admettra jamais en public l’impact de ces sanctions. Quand son bateau coulera et que seule sa main sera encore à la surface, Poutine continuera à crier que tout va bien et que les sanctions ne sont pas efficaces!

Poutine est dans une voie sans issue. Mais en Russie, d’autres personnes écoutent. Depuis trois ans, la stratégie du Kremlin est de dire aux élites et au peuple russe : attendez, ne vous inquiétez pas, cela ne va pas durer longtemps, les Européens sont faibles et incapables de tenir leurs paroles, tenez encore un peu. Mais cela dure. Si l’Europe renforce ses sanctions, cela va finir par semer le doute parmi ces élites politiques. Peut-être pas le premier cercle de Poutine, les criminels de guerre qui savent que, pour eux, il n’y a pas de porte de sortie. En revanche, le deuxième cercle, qui un jour sera sûrement au pouvoir – car le temps joue contre Poutine, il va devenir plus vieux et petit à petit la nouvelle génération arrivera au pouvoir – : observe l’évolution de la situation. Ils se demandent comment cela va finir : “Dans quelle Russie nos enfants vivront?”

D’après moi, c’est ce qui manque aujourd’hui à la stratégie européenne : envoyer un message aux élites futures en Russie. Plutôt que de dire à tout le monde : “vous êtes tous responsables de cette guerre, vous allez la payer pendant des générations”, laisser une porte ouverte à cette nouvelle génération pour leur dire que s’ils ont un projet de paix pour la Russie, rentrent dans le cadre du droit international et de la souveraineté de leurs voisins, ils peuvent offrir un autre futur à leur pays. Ce message n’existe pas et pire, aujourd’hui il y a plutôt un message qui soude les élites autour de Poutine, y compris les jeunes générations, qui se disent : “les Européens nous détesteront pendant des siècles et des siècles”. On peut formuler un message qui divise davantage les élites russes. Pour leur montrer que ce que Poutine martèle à longueur de journée – qu’il n’y a pas d’autre solution que la guerre totale avec l’Europe – est complètement faux.

Pendant qu’il fait mine de vouloir négocier, Poutine continue de pilonner l’Ukraine, et se réarme. Sous couvert de négociations, prépare-t-il la guerre d’après?

La guerre est devenue la raison d’être du régime de Poutine, je vois mal comment il peut rétropédaler aujourd’hui après tout ce qu’il a dit contre l’Europe et “l’Occident collectif”. Comment peut-il revenir en arrière et cohabiter pacifiquement avec l’Occident?

Le Poutine d’aujourd’hui est très différent du Poutine de 2012. Aujourd’hui, c’est un homme de guerre. Il a transformé la société russe, formé une minorité belliqueuse très motivée par cette guerre contre l’Occident et par l’idée de se venger de l’effondrement de l’URSS. Il mène par ailleurs une guerre hybride en Europe. Il est capable de mener d’autres “opérations militaires spéciales” sur d’autres cibles européennes. Mais pour cela, il faudrait d’abord qu’il parvienne à geler le front en Ukraine dans un accord de type “Minsk 3” [les premiers accords de Minsk sont des accords de cessation des hostilités entre la Russie et l’Ukraine signés en 2014 et 2015]. Aujourd’hui, l’armée russe patine en Ukraine. Faire la guerre sur deux fronts me semble peu probable. Par contre, s’il parvient à geler le front et à dégager une partie de son armée, il peut chercher des objectifs à l’ouest de la Russie.

Cela dépendra aussi du comportement de l’Otan. Car si la Russie cible la Finlande ou les Etats baltes, cela déclenche en théorie une guerre entre elle et l’Otan. Ce scénario paraît inimaginable aujourd’hui, on se dit que jamais Poutine n’attaquera l’Otan. Je dirais que ça l’est si l’Organisation transatlantique demeure une force crédible, cohérente et fiable. Quand on lit la presse russe aujourd’hui, une petite musique monte sur la crédibilité affaiblie de l’Otan en raison du désengagement des Américains. Les médias parlent beaucoup du retrait des troupes américaines de l’Europe. C’est un feu vert pour Poutine, qui ne croit pas en la résistance européenne.

Comment interprétez-vous les images satellites qui montrent la construction d’entrepôts, de tentes pour l’armée russe à la frontière finlandaise?

La stratégie de Poutine reste la guerre totale contre l’Europe. S’il ne semble pas en position de lancer une deuxième guerre aujourd’hui, il peut très bien être au stade des préparatifs : rassembler du matériel et des troupes près de la frontière, tout en semant la peur en Finlande pour se venger de l’adhésion du pays à l’Otan, perçue comme une trahison.

Comment envisagez-vous l’année 2025? Les plus optimistes espéraient une accalmie sur le front ukrainien, on en est encore loin…

Les nombreux changements tectoniques dans la géopolitique mondiale ne semblent pas affecter la détermination de Poutine à poursuivre sa guerre, devenue l’assurance-vie de son régime. Jusqu’à présent, tous les efforts de Trump, président naïf et incompétent, de mener des négociations, ont abouti à zéro. Poutine n’a aucun intérêt à cesser le feu à ce stade. Il a besoin d’une petite victoire, au minimum. S’il n’arrive plus à continuer cette guerre et a besoin d’une pause pour reconstituer ses ressources et ses troupes, il lui faudra à tout prix cette petite victoire pour expliquer à sa population pourquoi il a entraîné la Russie dans cette guerre, pourquoi tant de gens sont morts au front, pourquoi la Russie est isolée, sous sanctions. C’est pourquoi il y a une telle pression aujourd’hui dans le Donbass, car à mon avis c’est l’objectif de Poutine en 2025 : prendre entièrement cette région. Son problème, c’est qu’il n’y arrive pas. Trois ans après l’invasion à grande échelle de l’Ukraine, il contrôle environ 70 % du Donbass. S’il parvient à mettre la main sur toute la région, je n’exclus pas qu’il cherche à signer des accords de “Minsk 3” avec l’Ukraine.

The Economist, 23 mai

After the call : Donald Trump dashes any hope that he will get tough with Russia

He has nothing but kind words for Vladimir Putin

Full text :

IN THE HOURS before Donald Trump picked up the phone on May 19th to speak to Vladimir Putin, European diplomats believed that they were inching closer to alignment with the Americans on Ukraine. The American president had advertised the call as “turkey time”, a last-chance call for the Kremlin to end the war or face pain in the form of tough new sanctions. By the time the two-hour call ended, and European leaders joined a debrief with Mr Trump, it became clear that no threat had been issued to the Russian leader. Mr Trump hinted he would instead simply walk away from the negotiating process if he could not get the two sides to agree quickly, which in the absence of new pressure now appears likely. “I think something’s going to happen,” Mr Trump told reporters, though without providing a shred of justification for this optimism. “And if it doesn’t, I’ll just back away and they’re going to have to keep going.”

Many close to Volodymyr Zelensky, the Ukrainian president, have long believed that Mr Trump would be difficult to win over. But ever since the disastrous first February meeting in the Oval office, they have adopted a strategy of placating Mr Trump, while moving strictly in lockstep with European advisers. They have made several concessions in pursuing the goal of a ceasefire followed by meaningful negotiations. This includes dropping their demands for security guarantees before talks could start; imposing no conditions on a suggested ceasefire; signing a minerals and economic partnership deal; and flying to Turkey for talks that were less talks than a Russian declaration of a “forever war”.

The call appeared to vindicate the most sceptical in Mr Zelensky’s team. Despite promises to act tough, Mr Trump smothered Mr Putin with flattery and affection. “No one wanted to put down the receiver first,” is how one Kremlin adviser, Yury Ushakov, described an exchange that was light on detail and heavy on pledges of future economic co-operation. Mr Trump insisted that his call had achieved a new Russian agreement to work on a “memorandum” for peace, and on “immediate” talks. There was also the promise of new mediation by the Vatican. “Maybe that will be helpful. There’s lots of bitterness,” said Mr Trump. But a source close to Mr Zelensky says that Mr Trump sounded more as though he was crafting an exit strategy after understanding that he would struggle to achieve a breakthrough.

The Vatican has already confirmed that it is ready to host any new negotiation. A working group has been established with the Ukrainians, and there is an offer to do the same with the Russians. Mr Putin may well be attracted by the opportunity to validate himself by talking peace in Europe even while charges of war crimes hang over him. But he must surely know there is a downside to presenting heavily belligerent policies in such a holy setting. At the time of printing, the Russians had not agreed to the venue, or to anything as straightforward as a date or a format.

Describing Mr Trump’s U-turn on sanctions as a “bump in a very bad road”, one Western diplomat insisted that Mr Trump had yet to come to a final decision about his future involvement. What an exit could mean in practice is also hard to say: temporary or permanent; a partial exit or a full betrayal? Many other demands make calls upon Mr Trump’s time: the various crises in the Middle East, his “big beautiful” tax-cuts bill and his continuing tariff battles with much of the world. Prioritising these things does not necessarily mean he will cut off the flow of intelligence to Ukraine, or halt the supply of military equipment that is scheduled to keep flowing until at least the summer.

Ukraine’s backers hope Mr Trump may once again defy expectations. Perhaps in “withdrawing” from the process, he will allow Congress to vote through a sanctions package that would target Russian energy exports by hitting those who buy them with tariffs of up to 500%. Insiders say that the package already has enough signatures in the Senate to be passed; but it would still require Mr Trump’s approval. It is not impossible. But it is also hard to imagine it from a man who, whenever faced with Russian intransigence, has so far responded by tightening the screws on Ukraine. ■

Le Figaro, 23 mai

En Ukraine, les frappes russes sont désormais plus meurtrières et ciblent les civils loin du front

DÉCRYPTAGE – L’armée russe utilise des bombes programmées pour exploser en altitude au-dessus de zones civiles afin d’optimiser leur effet létal sur les populations, dénonce une enquête de l’ONG Human Rights Watch.

Full text :

Les attaques russes contre la population ukrainienne ont franchi un nouveau cap alarmant. L’armée de Moscou utilise désormais des munitions qui explosent en altitude au-dessus des zones civiles, amplifiant par là même leur effet létal sur de vastes périmètres. Entre janvier et avril 2025, ces frappes ont causé 57% de victimes civiles supplémentaires par rapport à la même période de 2024, révèle ce mercredi une enquête de l’ONG Human Rights Watch (HRW).

Cette analyse, fondée sur vingt témoignages directs, lectures d’images satellite et vérifications de vidéosurveillance, établit que ces attaques suivent systématiquement le même modus operandi : elles frappent à des heures de forte affluence, loin du front, sans objectif militaire significatif à proximité. Pour les juristes de HRW, ces attaques constituent des crimes de guerre au sens du droit international.

Le 4 avril dernier, à 18h50, une bombe russe explose ainsi au-dessus d’un parc de Kryvyi Rih, une ville du sud de l’Ukraine. «Cinq à dix secondes après l’explosion, j’ai entendu les cris les plus terribles de ma vie», témoigne Viktor Strochuk, habitant du quartier qui a tenté de secourir une femme âgée. «Je voyais un os qui sortait de son bras droit». Bilan : 20 civils tués, dont 9 enfants, et 73 blessés, incluant un nourrisson de trois mois. L’ONU la qualifie de «frappe la plus meurtrière contre des enfants depuis le début de l’invasion russe».

HRW a vérifié sept enregistrements de vidéosurveillance autour d’un restaurant dans le périmètre touché par cette explosion. Les images témoignent qu’une fête anniversaire entre adolescents venait de s’achever à 18 heures, au moment de la frappe. Ces mêmes vidéos prouvent en revanche l’absence totale de militaires sur place. Ce qui n’empêchera pourtant pas le ministère russe de la Défense de revendiquer avoir éliminé «85 militaires» dans ce restaurant.

Des frappes jusqu’à 240 km du front

L’enquête de l’ONG documente une frappe particulièrement révélatrice à Poltava, située à 240 km du front. Le 1 er février, à 7h44 précises, un missile a détruit un immeuble d’habitation, faisant 15 victimes civiles. L’explosion pulvérise 1500 fenêtres dans un rayon de 270 mètres, endommageant 308 foyers et blessant 528 résidents, selon les chiffres d’une organisation caritative locale.

Ludmila Novitska, 71 ans, préparait ce matin-là son petit-déjeuner : «Quelque chose a soudainement explosé. Un bruit assourdissant, puis de la fumée. Ma chambre a été entièrement détruite. Si j’y avais été, je serai morte.» Autre exemple fournit par HRW : le 4 février 2025, à 11h36, dans la ville d’Izium, une frappe russe touche un bâtiment administratif, à un kilomètre de toute installation militaire, faisant 6 morts et 57 blessés, dont 3 enfants.

Face à cette menace, les Ukrainiens ont mis en place des veilles nocturnes et surveillent en permanence les chaînes Telegram annonçant les alertes aériennes. «Mon mari a vérifié l’activité des missiles dans la région sur Telegram à 3 heures du matin», témoigne une survivante de Poltava, dont l’appartement a été entièrement détruit. «Nous avons lu qu’un missile X-22 se dirigeait vers notre ville, alors nous nous sommes réfugiés dans l’abri».

HRW souligne qu’aucune des quatre attaques qu’elle a documentées n’a été précédée d’un avertissement aux civils, contrairement aux obligations découlant du droit international humanitaire. L’ONG rappelle que les commandants militaires et les dirigeants civils peuvent être poursuivis pour crimes de guerre lorsqu’ils savaient ou auraient dû savoir que des crimes étaient commis sans prendre de mesures pour s’y opposer.

«Les efforts diplomatiques pour mettre fin à la guerre devraient donner la priorité à la protection des civils et à la justice», souligne Belkis Wille, directrice associée crises et conflits à HRW. «Cela signifie, insiste-t-elle, qu’il ne peut y avoir «d’amnisties pour ceux qui ont commis de graves violations du droit international humanitaire».

The Wall Street Journal, 22 mai

Trump Tells European Leaders in Private That Putin Isn’t Ready to End War

U.S. president made the acknowledgment after speaking to the Russian leader this week but backed off on additional sanctionsFull text :

On a call Monday, President Trump told European leaders that Russian President Vladimir Putin isn’t ready to end the Ukraine war because he thinks he is winning, according to three people familiar with the conversation.

The acknowledgment was what European leaders had long believed about Putin—but it was the first time they were hearing it from Trump. It also ran counter to what Trump has often said publicly, that he believes Putin genuinely wants peace.

The White House declined to comment and referred to Trump’s social-media post on Monday about his conversation with Putin. “The tone and spirit of the conversation were excellent. If it wasn’t, I would say so now,” he said.

Although Trump appears to have come around to the idea that Putin isn’t ready for peace, that hasn’t led him to do what the Europeans and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky have been arguing he should do: double down on the fight against Russia.

Trump had held an earlier call with European leaders on Sunday—a day before his two-hour conversation with Putin. He had indicated then that he could impose sanctions if Putin refused a cease-fire, according to people familiar with the conversation.

By Monday, he had shifted again. He wasn’t ready to do that. Instead, Trump said he wanted to proceed quickly with lower-level talks between Russia and Ukraine at the Vatican.

President Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin spoke for more than two hours but failed to agree on an immediate cease-fire in Ukraine. WSJ National Security Reporter Alexander Ward unpacks the call. Photo Illustration: Reuters/Associated Press

The call Monday included Zelensky, French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. It was in part the culmination of a European diplomatic offensive that had started some 10 days earlier, aimed at getting Trump to put pressure on Putin.

While the effort ultimately didn’t succeed in getting Trump to do that through additional sanctions, Europeans saw some upside to the outcome. The process had helped clarify for everyone, including Trump, where Putin stood: He is unwilling to halt the war at this stage. And for the Europeans, it helped underscore that it was now largely up to them to support Ukraine. Europeans don’t believe the Trump administration will stop U.S. weapons exports as long as Europe or Ukraine pays for them, the people said.

“This isn’t my war,” Trump told reporters on Monday after his Putin call. “We got ourselves entangled in something we shouldn’t have been involved in.”

Trump had indicated in a call with European leaders Sunday—which included Macron, Merz, Meloni and U.K. Prime Minister Keir Starmer—that he would dispatch Secretary of State Marco Rubio and special envoy Keith Kellogg to talks that are now expected to take place at the Vatican. On Monday, Trump appeared to be noncommittal about a U.S. role, according to one of the people briefed on the call.

Some of the Europeans on the call Monday insisted that the outcome of any talks at the Vatican must be an unconditional cease-fire. But Trump again demurred, saying he didn’t like the term “unconditional.” He said he had never used that term, although he used it when calling for a 30-day cease-fire in a post on his Truth Social platform on May 8. The Europeans eventually agreed to drop their insistence on the adjective.

Europe’s diplomatic offensive to get Trump to pressure Russia escalated when Merz, the conservative German chancellor, took office earlier this month. Merz has been much more willing to confront Putin than his left-leaning predecessor, Olaf Scholz. More important, Merz’s coalition helped amend Germany’s constitution to allow the country much greater latitude in borrowing to spend on the military and support for Ukraine.

On May 10, Merz, Macron, Starmer and Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk paid an impromptu visit to Zelensky in Kyiv. They urged him to go along with what Trump wanted, to expose Putin’s unwillingness to end the war. They then used Macron’s cellphone to call Trump from Zelensky’s official residence, telling him Europe and Ukraine were fully behind his call for a 30-day cease-fire. The Europeans publicly threatened new sanctions against Putin if he didn’t accept the cease-fire.

Putin responded to the rising pressure from Europe and Washington by proposing the first direct negotiation with Ukraine in three years. Trump seized on the offer, even at one point suggesting he could go to Turkey to join the talks.

A meeting took place in Istanbul within days, but Putin didn’t attend. He dispatched lower-level representatives who repeated demands that Ukraine deems unacceptable.

After Putin’s no-show in Istanbul, the Europeans again pressed Trump to consider putting more pressure on the Russian leader. They approved modest new sanctions against Russia but continue work on a stronger package of measures. Trump announced he had set up a call with Putin, saying peace prospects could only be advanced if the U.S. and Russian leaders spoke.

When Trump spoke Sunday with European leaders, ahead of that Putin call, he signaled the U.S. might join Europe in sanctioning Russian energy exports and bank transactions. Sen. Lindsey Graham (R., S.C.), a close ally of Trump, said Wednesday he had gathered 81 co-sponsors for a bill that would significantly ratchet up energy and other sanctions on Moscow.

That Sunday call included some of Trump’s signature off-the-cuff style, mixing praise and criticism of European leaders. He complimented Merz on his beautiful English. “I love it even more with your German accent,” he said, according to a person on the call.

At another point, he digressed into a broadside against Europe’s migration policies. Trump said out-of-control migration was bringing their countries to the “brink of collapse.”

Macron, who has the longest relationship with Trump, asked him to stop. “You cannot insult our nations, Donald,” said Macron, according to the person on the call.

The tone, however, was positive overall, said the people familiar with the call. It left some with the impression that Trump just might support fresh sanctions if Putin didn’t agree to a cease-fire. But those hopes were dashed a day later.

The talks in the Vatican are expected to start in mid June.

https://www.wsj.com/world/europe/trump-putin-call-russia-ukraine-83a6ef59?mod=hp_lead_pos3

The Wall Street Journal, 22 mai

Oil Sanctions Would Hit Russia Harder Now Than in 2022

Demand is growing slowly while supply is increasing faster than usual. That’s bad news for Putin.

Full text :

Despite Western efforts otherwise, Russia is still able to finance its aggression in Ukraine by selling oil three years after its invasion. When the war began, the global economy’s dependence on a tight energy market complicated the West’s work to limit Vladimir Putin’s revenue. In 2022, seriously reducing Russian oil exports would have rendered energy prohibitively expensive for consumers and businesses across the globe. But changing market conditions have simplified matters. Now is the time to take Russian oil off the market and shrink the Kremlin’s war chest.

The West so far has had to settle for a Group of Seven price cap on Russian oil. This solution, on which I worked with colleagues in the Biden administration, kept Mr. Putin from profiting from Russia’s aggression as much as he could have. The price cap took advantage of the G7’s influence over maritime services to permit only Russian oil sales below $60 a barrel. The idea was to maintain the volume of Russian oil exports and avoid market disruption while limiting the Kremlin’s revenue.

The price cap had a banner first year as Russian revenue fell while the country’s export volumes held steady. But its effectiveness later dwindled as the Kremlin invested in new shipping infrastructure to evade the cap and Western enforcement proved inconsistent for fear of spooking markets. The price cap was an imperfect but nuanced response to a complex trade-off.

That trade-off has now gotten easier. Oil analysts are worried today more about oversupply than shortage, as oil production rises and demand slows globally. The risk of a decrease in oil supply disrupting the global economy is much lower.

Total demand for oil rose about 2 million barrels a day in 2022 and rose about the same in 2023, according to the International Energy Agency. But in 2024, that pace halved, to around 900,000 barrels a day; and in 2025, the IEA expects only 700,000 barrels a day in new demand. Sluggish Chinese demand explains much of the shift, as China’s growth slows and its transportation sector electrifies. U.S. tariffs would further crimp energy demand, as will the uncertainty surrounding their potential implementation.

Meanwhile, oil supply is growing faster than usual, largely driven by more oil production from non-OPEC+ countries. Back in 2022, the OPEC+ cartel, which includes Russia and Iran, produced about 60% of global oil. In 2025 the IEA expects supply from non-OPEC+ countries such as the U.S. and Canada to rise by 1.3 million barrels a day in 2025, almost double the amount needed to offset the IEA’s projected increase in demand. We can afford to lose some Russian supply without disrupting markets.

The economy this year has already aced an important test of its resiliency to tougher action against Russian oil. In January, the Biden administration imposed wide-ranging sanctions to enforce the cap more strongly. Brookings economists found that this had no significant market impact and that room remained for further sanctions “without any meaningful spike in global oil prices.”

The West has several options to take Russian oil off the market. The G7 could simply lower the price cap. Or it could ban any G7 business from servicing the Russian oil trade at any price—essentially lowering the cap to zero. But the new shipping infrastructure Russia has built to evade the price cap could limit the effectiveness of either approach.

There is a bolder option. The West could impose sanctions on anyone who buys Russian oil, using its full might to shrink the Kremlin’s exports—what policymakers call secondary sanctions. The U.S. could lead the effort, or the European Union and U.K. could take this step without American collaboration. If such a strategy removed 2 million barrels a day from the market—only one-fourth of Russian oil exports—I estimate based on economists’ models that Kremlin oil revenues would plummet 20% while lifting gasoline prices only 15 cents a gallon. That is an excellent bargain. Retail gasoline prices have already fallen 50 cents over the past year.

Secondary sanctions support American and European interests in the broader geopolitical context. China is one of Russia’s major energy customers and benefits from discounted Russian oil. Secondary sanctions would hinder Beijing’s windfall. They would also increase the West’s leverage in the stalled Ukrainian peace talks.

Secondary sanctions wouldn’t eliminate the Russian oil trade; oil barons are a resourceful bunch. But taking even some oil off the market would hit Kremlin coffers where it is most painful.

There are always risks in restricting an adversary’s energy supply. But today’s market dynamics offer the best opportunity—since the war began—to hold Mr. Putin accountable.

Mr. Van Nostrand served as chief economist of the U.S. Treasury, 2023-25.

L’Express, 22 mai

Guerre en Ukraine : la brigade “Anne de Kiev” de nouveau dans la tourmente

Invasion russe. La 155e brigade, formée et équipée par la France, est au cœur d’un nouveau scandale pour malversations et désertions.

Full text :

Elle devait être un modèle de la modernisation de l’armée ukrainienne, mais se retrouve à nouveau dans la tourmente. La brigade “Anne de Kiev”, formée et équipée par la France, est sous le coup d’une enquête de l’armée ukrainienne, qui la soupçonne de malversations et désertions, a annoncé ce mardi 20 mai la presse ukrainienne. Le commandant des forces terrestres ukrainiennes, Mykhailo Drapatyi, a ordonné une inspection de la 155e brigade, dont le colonel, Taras Maksimov, est soupçonné d’avoir mis en place un système de pots-de-vin.

Nouvelle controverse

Un “officier aurait exigé des versements de ses subordonnés contre des primes falsifiées pour leur prétendue participation aux combats en première ligne”, indique le média ukrainien Ukrainska Pravda. L’enquête interne révèle également “1 200 abandons de poste depuis 2025” (alors que la brigade compte moins de 5 000 soldats) et “un manque d’approvisionnement suffisant de l’unité”, précise le média ukrainien.

Depuis son déploiement sur le front, la brigade, dont la moitié des soldats ont été formés en France, multiplie les controverses concernant des pénuries d’équipements, notamment des drones, et des désertions en masse parmi ses soldats. En 2024, l’armée avait déjà ordonné un changement de commandement après une enquête pour mauvaise gestion. Le commandant de l’époque, le colonel Dmytro Riumshyn, avait été limogé et incarcéré.

“Modernisation militaire”

La brigade avait initialement été conçue comme un projet phare pour la modernisation militaire ukrainienne, et avait reçu l’aide de la France et d’autres partenaires étrangers dans sa guerre contre l’invasion russe. Mais dès son déploiement sur le front, elle avait fait l’objet de critiques, accusée d’avoir utilisé ses soldats pour “colmater les trous” dans d’autres unités.

Environ 2 300 des soldats de la brigade ont été formés sur le sol français et équipés de véhicules de transport français VAB, de chars AMX-10 et de canons automoteurs Caesar, ainsi que de munitions et de missiles antiaériens et antichars. Le président français Emmanuel Macron avait rendu visite en octobre 2024 aux soldats de la 155e brigade ukrainienne pendant leur entraînement en France.

Le Figaro, 21 mai

En exigeant une reddition de l’Ukraine, Vladimir Poutine campe sur sa position maximaliste

DÉCRYPTAGE – La Russie refuse tout cessez-le-feu et exige des concessions inacceptables pour Kiev.

Full text :

Dans la nuit de samedi, la Russie a lancé l’une des plus importantes attaques de drones sur l’Ukraine, frappant de nombreuses villes et cibles civiles, tuant une femme à Kiev. Ce raid intervient tout juste deux jours après des pourparlers directs entre Russes et Ukrainiens qui se sont tenus à Istanbul, sous médiation turque. Ce dialogue, le premier depuis trois ans, n’a débouché sur rien, ou presque.

Comme si ces bombardements massifs n’étaient pas suffisants, dimanche matin, Vladimir Poutine, dans un entretien à la télévision, a entériné cet échec en affirmant qu’il entendait « éliminer les causes qui ont provoqué cette crise, et créer les conditions d’une paix durable ainsi que garantir la sécurité de l’État russe ». Pour le président russe, cela signifie généralement exiger une reddition de l’Ukraine. Moscou campe sur ses positions maximalistes. À Istanbul, les négociations, qui n’ont duré qu’à peine deux heures, ont mis en lumière ses exigences extrêmes.

Crimée annexée

Les Russes réclament, l’arrêt des livraisons d’armes occidentales, que l’Ukraine renonce à rejoindre l’Otan et l’abandon total, outre de la Crimée annexée en 2014, des quatre régions qu’ils ne contrôlent que partiellement. Cela revient à demander que les Ukrainiens se retirent de grandes villes reprises, comme Kherson, voire cèdent des cités jamais envahies, comme Zaporijjia, ou des infrastructures énergétiques majeures. Des conditions évidemment inacceptables pour Kiev, qui, de son côté, réclame un cessez-le-feu « inconditionnel » et une rencontre entre les présidents des deux pays.

Seule avancée : un accord pour un échange de 1000 prisonniers de chaque camp qui pourrait avoir lieu cette semaine. Le reste des discussions n’a fait que mettre en évidence le fossé béant qui ne fait que se creuser après trois ans de conflit.

Pourtant nul n’attendait plus grand-chose de cette rencontre, alors que la délégation russe était menée par un second couteau, l’ancien ministre de la Culture Vladimir Medinski. L’arrivée des Russes à Istanbul apparaît essentiellement comme une petite concession aux pressions de Donald Trump, qui entend obtenir un cessez-le-feu inconditionnel de 30 jours. Une demande acceptée par Volodymyr Zelensky. Ce dernier s’est rendu dimanche à Rome, où le pape Léon XIV, qui a évoqué place Saint-Pierre « l’Ukraine martyrisée » dans l’attente de « négociations pour une paix juste et durable », l’a reçu en audience privée.

Bonne volonté

Cette fin de non-recevoir russe ne semble pas avoir lassé le président américain qui a affirmé samedi vouloir parler par téléphone lundi à son homologue russe. L’objectif de cet appel est de « mettre fin au bain de sang », a dit Donald Trump sur son réseau Truth Social. Un tel dialogue entre les deux chefs d’État est un nouveau pas en direction de Vladimir Poutine, qui, sans céder sur rien, est en passe de voir écartés des discussions la partie ukrainienne mais aussi les Européens.

Pour Donald Trump, seule une rencontre entre lui et le leader russe serait à même de débloquer la situation quand bien même Moscou ne montre pas le moindre signe de bonne volonté. Le chef de la diplomatie américaine, Marco Rubio, présent à Istanbul, s’est lui entretenu samedi avec son homologue russe, Sergueï Lavrov, resté pour sa part en Russie. Selon le secrétaire d’État, Moscou préparerait un document comprenant les exigences russes en vue d’un cessez-le-feu.

The Guardian, 19 mai

Sergei Lebedev: The USSR occupied eastern Europe, calling it ‘liberation’ – Russia is repeating the crime in Ukraine

In the post-Soviet states, statues can be removed and street names changed. But achieving sovereignty of memory is far harder

Full text :

We often hear that it is Russia’s inability or unwillingness to deal with the crimes of its past that has led to the restoration of tyranny and the military aggression that we see now. Such a narrative usually focuses only on internal Soviet deeds: forced collectivisation, the Great Terror of the 1930s, the Gulag system and so on. Some of these things were nominally recognised as crimes, but no attempt was made to hold the perpetrators to account. Russia’s perestroika democrats were generally opposed to transitional justice.

However, the most politically sensitive Soviet crime is nearly always left out of the discussion. And Russia’s failure to address this particular crime is far more dangerous and affects the fate of many nations.

That crime is the Soviet occupation of central and eastern Europe, which lasted for decades and resulted in many dead and arrested, the destruction of social and cultural life and the denial of freedom. The injustice was immense.

Internal Soviet crimes, which went unpunished, were at least legally acknowledged and their victims commemorated. External aggression and occupation were not. Аnd even Russian dissidents and liberals never risked raising the issue.

This is why, in relation to central and eastern Europe, there are two concepts of memory and history that normally cannot coexist, that clash with and contradict each other. They are totally opposed; they cannot be reconciled by diplomacy: Soviet liberationversus Soviet occupation.

It was only when Soviet troops finally withdrew from eastern and central Europe 45 years after the end of the second world war that the true liberation came, when the Soviet Union collapsed and occupied nations found their way to independence. But it was easier to restore or establish statehood and independence than to achieve sovereignty of historical memory.

The progressive image of theSoviet Union in its final days, the high hopes of the moment, shielded Moscow from serious criticism and accusations related to the occupation of eastern Europe. This restraint was the result of a surfeit of trust or, maybe, just cautionary pragmatism – the desire not to irritate Moscow and undermine its goodwill, not to burden the losers of the cold war too much. But the most important protection Moscow enjoyed was, of course, based on the status of having been victorious over nazism.

Russia, as the self-proclaimed successor state to the USSR, has built its international political profile on the Soviet liberation myth, which provides moral capital and prescribes to the former occupied territories a debt of gratitude for their “liberation” from nazism.

Yes, the Soviet losses were real. And yet it is truly tragic that these losses helped to subjugate nations longing for freedom, replacing one dictatorship with another. The Soviet soldier, memorialised in statues that still mark the landscape of Europe from Berlin to Sofia, was not a liberator. He was an enslaver. And no amount of bloodshed by the Soviets to defeat the Nazis can excuse the Soviets’ own role as occupiers.

It is not accidental that the Soviets were reluctant to recognise even the existence of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. In modern Russia, to make any equivalence between the roles of the USSR and the Nazis is criminalised. In 1939 and 1940, the Soviet Union occupied Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, and parts of Poland, Finland and Romania. For 22 months it was a faithful ally of Nazi Germany. This first wave of Soviet occupations can in no way be disguised as a “struggle against nazism”: it revealed the real intention of the Soviets. What then followed, was, in fact, a geographically extended reoccupation. This was a separate aim of the war, not necessarily connected to the one to defeat the Nazis.

Unfortunately, understanding the Soviet occupation as a crime has not become an essential part of modern European history. It is geographically limited to the east, blurred, insufficiently represented; it forms part of the histories of individual nations but it does not form a powerful international narrative shared across the continent. Yet this understanding has a profound bearing on modern European life and is key to European security. Only when you fully grasp the cruelty and consequences of the Soviet occupation can you comprehend the concerns of Russia’s closest neighbours, their historically grounded fears and their need for safety.

Eastern regions of Ukraine are now occupied by Russian troops. For the first time since 1989, large areas of the European continent, home to millions of people, are under the control of an invading state. But it seems that too many Europeans have already forgotten what occupation means.

Russian citizenship is being forcibly imposed. In fact, this is a mass expulsion programme, because those who do not agree will be treated as foreigners and forced to leave. Russia is pursuing the same path as the USSR did, for example, in relation to the Baltic states, aiming to Russifythe conquered region, rearrange its national composition and make it a part of its state.

Property is being confiscated and redistributed. “Settlers” are brought in to form the backbone of the occupation regime. The politics of memory are reversed, monuments marking Soviet crimes disappear, streets are given back their Soviet names as a symbol of Russian domination. All this is part of an attack on national identity, an attempt to erase it.

The Russian state security services use filtration techniques extensively, and anyone deemed politically unreliable can be imprisoned. Severe torture and sexualised violence are widespread. Ukrainian prisoners of war released from captivity report the same torture, abuse and deliberate malnutrition aimed at breaking them physically and mentally.

Anyone who knows the history behind the iron curtain immediately recognises the pattern. All this was a grim reality for Poland and Lithuania, East Germany and Romania and others. Mass deportations, the brutal rule of the secret police, deprivation of property and civil rights … but it never became a real stigma for the USSR or, later, Russia. It never became something of which a nation is ashamed, something that demands justice and punishment, acknowledgment and atonement.

And this is where weare now: the occupier is back. And the occupier wages war exactly like the Soviets did.

Vladimir Putin’s army has a gruesome advantage over western armies, which have invested heavily in keeping their personnel out of harm’s way. It can sustain losses that would be absolutely unacceptable for any western country. But it is also technically advanced enough to counter western military technologies.

Western science was the first to “dronise” warfare, to minimise the involvement of troops on the ground and use machines for new tasks. Putin’s army, while also using real drones, dronises human beings as well. It has turned soldiers into dispensable, single-use units.

With Russia’s full-scale invasion we have entered the era of global moral climate change. Just as one earthquake can have repercussions all over the world, or a single volcanic eruption can pollute the skies above several continents, Russia’s aggression changes the political climate worldwide.

This is another very real, but not yet fully recognised, outcome of the war. It is perhaps the most wide-ranging of all the outcomes. With thousands of troops sent into battle and killed by Ukrainians defending themselves, Putin doesn’t just get some pieces of Ukrainian territory – he erodes the political landscape worldwide, upsets alliances, exhausts the patience of voters in Nato countries and drags us down into the hell of moral relativism.

What can be done about it?

Western and south-western Europe, which never faced the reality of Soviet occupation, must now listen to the voices of those who experienced it first-hand.

It is hard to say whether Russia will be held accountable for its crimes against Ukraine any time soon. But to build a future at all, a real future, it will be paramount to develop a cultural and historical concept countering Russia’s attempt to divide and rule.

On the initiative of Václav Havel, Joachim Gauck and other prominent former dissidents, 23 August, the date of the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, is the EU’s Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism, or Black Ribbon Day. Understanding of the significance of this day could and should be deepened to include a broader perspective on Russian imperialism, which was part of Soviet communist policy but has outlived it.

We need to make this day the focus of a long-term and coordinated politics of remembrance, to strengthen existing institutions such as ENRS – the European Network Remembrance and Solidarity, which includes mostly eastern European countries. We must also build new ones, across continents, countering both leftwing and rightwing narratives that continue to make excuses for Russia.

The USSR collapsed because its artificial unity was enforced by violence and oppression. The EU’s endurance depends on the persistence of its voluntary unity. But unity is not a given. It is a product of mutual knowledge and compassion, of many cultural bridges connecting people.

It is time to start building.

This article is adapted from the writer’s closing address at the Helsinki Debate on Europe, 18 May 2025

Sergei Lebedev is an exiled Russian novelist. Since 2018 he has lived in Potsdam, Germany. His latest novel is The Lady of the Mine (2025)

The Wall Street Journal, 19 mai

Putin’s Plan to Outlast Ukraine and the U.S.

Russia’s leader ‘blossoms whenever he talks about war’ and hopes Trump will give up on a peace deal.

Full text :

After all the speculation about how Russian President Vladimir Putin would respond to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s offer to meet for peace talks in Istanbul, it isn’t surprising that Mr. Putin declined. Instead he sent a low-level delegation, headed by the ultraconservative former culture minister Vladimir Medinsky.

Having repeatedly declared Mr. Zelensky’s government illegitimate, Mr. Putin would have made a huge concession—and appeared weak—if he had met with Mr. Zelensky. More important, a meeting between the two, which President Trump had suggested he might attend as well, wouldn’t have achieved much. Mr. Putin relishes being a wartime leader and is determined to continue the conflict until Ukraine is coerced into becoming a “friendly” neighbor.