Back to Kinzler’s Global News Blog

The Economist, 9 mai

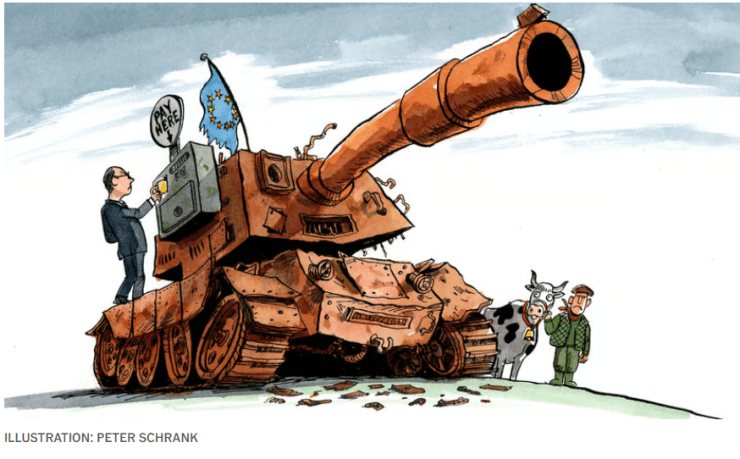

An existential struggle : What Putin wants—and how Europe should thwart him

Many Europeans are complacent about the threat Russia poses—and misunderstand how to deter its president

Full text:

IN RED SQUARE on May 9th Vladimir Putin is due to celebrate Victory Day, marking the defeat of Nazi Germany. The parade used to include Russia’s second-world-war allies. Today, as Mr Putin targets what he absurdly claims is another “Nazi” government in Ukraine, it signals how Russia stands resolutely against the West. That should worry all of Europe.

As the death toll in Ukraine has grown, Mr Putin’s war aims have swollen to justify Russian losses. What began as a special military operation next door has become Russia’s existential struggle against distant enemies. This is a profound shift. It means Ukraine’s future depends on Mr Putin’s ambitions more than President Donald Trump’s theatrical diplomacy. It also means that many Europeans are complacent about the threat Russia poses—and that they misunderstand how to deter him.

Russia may not be about to invade other parts of Europe. But it will try to gain sway by redoubling its cyber-attacks, influence operations, assassinations and sabotage. If Mr Putin senses weakness, he could seek to split apart NATO by seizing a small piece of territory and daring the allies to respond. He could be ready for that in two to five years. This may sound a long time. In military planning it is the blink of an eye.

Many people in America and southern Europe will find these claims hysterical. Some, like America’s envoy Steve Witkoff, say that Mr Putin can be trusted; or that he would not dare violate Mr Trump’s putative peace deal. Others, though wise enough not to trust a man who has gone to war five times in 25 years, argue that Russia is too weak to pose much threat. In Ukraine it has suffered almost 1m dead and wounded and, since its gains in the first weeks after the invasion, it has taken less than 1% more of Ukraine’s territory.

Many in the Baltic states, Poland and the Nordic countries go to the other extreme, warning that the threat is bigger than Mr Putin, because Russian imperialism has deep roots. That fear is understandable given their history of being mauled, but it is the wrong way to approach Russia. Not only does it affirm Mr Putin’s message that NATO is incurably anti-Russian, but it makes Europe more likely to miss chances for detente.

Mr Putin is indeed an aggressor who needs to be deterred. A bad peace imposed on Ukraine could become a springboard for his next war. At the same time, however, even if Mr Putin is implacable, he is 72 years old. Now is the moment to influence what comes after him.

Deterrence depends on understanding the threat Mr Putin poses. After three years of fighting, war has become an ideology. In the past, 60% of Russians said that the government’s priority should be to raise living standards. Today, that share has fallen to 41%; instead, 55% now say they want Russia to be respected as a world power. Mr Putin has put the whole of Russian society onto a war footing. The arms industry creates employment. Generous payments to soldiers and their families amount to 1.5% of GDP. Mr Putin also uses war as his excuse for ever-harsher repression and isolation from the West.

It is wrong to think that Russia’s forces are spent or incapable. The navy and air force are largely intact. NATO’s top commander says Mr Putin is restocking men, arms and munitions at an “unprecedented” pace. Russia plans to have 1.5m active troops, up from 1.3m in September; eventually, it could boost forces and kit on the western front by 30-50%. Thanks to the war, it has deepened its ties to China, Iran and North Korea.

Russian tactics are crude and costly, but a sudden small incursion into a NATO member would force NATO to choose whether to take back lost ground and risk nuclear war. If it did not fight, NATO would be broken. In a longer conflict NATO could surely repel a first Russian offensive, but would it have the resources for a fifth or sixth? Mr Putin might count it a strategic victory if Mr Trump declined to turn up, even if Russia were pushed back. That is because America’s absence on the battlefield would entrench Russia’s influence over Europe.

Defence against Russia begins in Ukraine. The more Mr Putin is denied success there, the less likely he is to attack NATO. As The Economist has argued, that means supplying Ukraine with arms, as well as giving it more money to pay for those it can build cheaply itself. Ukraine could produce $35bn-worth of kit a year, but has orders for less than half as much. Mr Trump should see that financing Ukraine is in America’s interests, if only because China is watching Russia’s progress.

However, backing Ukraine is not enough to make the entire continent safe and Mr Trump is unlikely to offer much help, so Europe must do more. That means working harder to defend itself, shoring up its unity and laying the foundations for a post-Putin Russia.

Europe is buying more arms. New figures from SIPRI, a Swedish think-tank, show that NATO, excluding America, increased spending by $68bn, or 19%, in 2022-23. More is needed, but European leaders have still not prepared voters for the sacrifices ahead. They are squabbling over arms contracts. For example, Britain may not be allowed to join a European Union scheme unless it lets EU boats fish in its waters.

Work is needed to enhance NATO’s unity, especially if America no longer binds it together. It is naive to think that countries like Spain and Portugal will ever fear Russia as Estonia and Poland do. But they face threats to their infrastructure and politics. They also have a vital interest in the EU being spared the dysfunction that would result from greater Russian influence over its eastern members.

Last, Europe needs a Russia policy that looks beyond Ukraine. In the cold war the West persuaded ordinary Russians that it was on their side, and that what kept them from freedom and prosperity was the Soviet regime. It cultivated dissidents and encouraged contacts. Today, too many Europeans are hostile to all Russians, rather than just the warmongers.

Europe has the wealth and industrial power to withstand Mr Putin. It has the potential to find an accommodation with his successor. As Russian soldiers strut through Red Square, the question is whether Europe can overcome its divisions in order to save Ukraine and protect itself. ■

https://www.economist.com/leaders/2025/05/08/what-putin-wants-and-how-europe-should-thwart-him

The Economist, 9 mai

Watching the bear : Would Vladimir Putin attack NATO?

Russia is building up its forces, causing fear in its neighbours

Full text:

EGERT BELITSEV, the head of Estonia’s border force, calls it the edge of the free world. A bridge stretches between the outer walls of the Hermann Castle in Narva, on the Estonian side, and those of the Ivangorod Fortress, in Russia. Swollen by the melting snows, the Narva river seethes underneath. Two giant screens recently erected on the Russian side facing Estonia were expected to stream video of the parade in Red Square on May 9th commemorating victory in the second world war. The sounds of drums and the images of goose-stepping Russian soldiers are bound to induce anxiety in Estonia, which was annexed in 1940 by Stalin and was occupied by the Soviet Union from 1944 until 1991.

Provocations are routine. Russia has been jamming GPS signals throughout the region, disrupting air traffic and search-and-rescue operations. Last year Russian border guards removed buoys on the Narva, which mark the border. Surveillance blimps are a regular sight in the skies. More concerning is what can be seen on satellite images. Although Russia’s bases near the Estonian and Finnish borders are nearly empty, with troops and equipment sent to Ukraine, new construction is under way.

On paper, Russia has big plans. It aims to expand its armed forces to 1.5m active troops, up from about 1.3m in September. In 2023 it announced the creation of a new formation, the 44th Army Corps, in Karelia, along the Finnish border. The 44th’s first units were bloodied in Ukraine last year. Russia is also expanding several brigades into larger divisions. All this will take years to accomplish. But if Russia succeeds, notes Lithuania’s intelligence agency, it will increase troops, equipment and weapons on its western front by 30-50%. “During 2024”, noted a recent Danish intelligence assessment, Russian rearmament “changed character from reconstruction to an intensified military build-up”. The goal is to be able “to fight on an equal footing with NATO forces”.

Some argue that Russia is bound to attack. “It’s a question of when they will start the next war,” argued Kaja Kallas last year, when she was Estonia’s prime minister (she is now the EU’s foreign-policy chief). Emmanuel Macron, France’s president, in March pointed to Russia’s breakneck rearmament. “How believable is it, then,” he asked, “that today’s Russia will stop at Ukraine?” Others are sceptical that Russian ambitions range much beyond the Dnieper river. Pedro Sánchez, Spain’s prime minister, scoffs at the notion of a big war: “Our threat is not Russia bringing its troops across the Pyrenees.” Steve Witkoff, Donald Trump’s envoy for peace talks with Russia, when asked whether Russia intended to “march across Europe”, responded simply: “100% not.”

Intelligence analysts frame threats in terms of two variables: intent and capability. There is no specific intelligence at present that suggests Russia intends to attack NATO. But intentions are fluid. In his public speeches, Vladimir Putin has justified his war to conquer Ukraine in several ways: the need to defend Russian-speakers in Donbas; the imperative of “demilitarising” and “de-Nazifying” Ukraine; and the need to keep a supposedly hostile NATO at bay. In February 2022, on the eve of war, Mr Putin blamed Lenin for tearing apart the Russian empire, implicitly casting doubt on the sovereignty not only of ex-Soviet states like Ukraine, but also of those once part of that empire, such as Finland.

Yet for Mr Putin, war may be less about external threats than about prolonging and trying to legitimise his reign. In his 25 years in power, he has waged five wars. Each began with his popularity sagging; each ended with his authority enhanced. At the start of the war few Russians believed the Kremlin’s line that Russia was threatened by the West. It has since become more widely accepted—not least because Mr Putin’s propaganda was reinforced by some Western rhetoric that blamed all Russians for the war. This has alienated those who were initially sympathetic towards Ukraine and the West.

Rallying round the flag

Though a majority of Russians would prefer the war to end, most also credit the war with boosting the country’s international clout, according to a joint survey conducted by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs and the Levada Centre in Moscow. In the past, 60% of Russians prioritised high living standards over great-power status. Today 55% of Russians favour power projection over high living standards. They may be getting part of their wish. After three years of war, Russia’s economy is sliding towards stagnation. Inflation remained stubbornly above 10% in the year to March despite the central bank holding its benchmark interest rate at 21%.

Sometimes it is capability that shapes intentions. In a recent interview, Mr Putin said that the war in Ukraine is the culmination of a long-standing confrontation with the West. After he grabbed Crimea from Ukraine in 2014 he stopped, not because he lacked the will to grab more, but because he lacked the means. “In 2014 the country wasn’t prepared for a head-on confrontation with the entire collective West, which is what we’re seeing now.”

Yet Mr Putin’s zest for war and his ability to wage it are two different things. In Ukraine his troops have spent nine months unsuccessfully assaulting Pokrovsk, with a pre-war population of 70,000 people, while suffering more than 1,000 dead and wounded every day. Russia’s army is incapable of complex manoeuvres and a generation of officers has been lost. Its air force rarely ventures into Ukraine, preferring to hurl glide bombs from a safe distance. As long as the war in Ukraine grinds on, Russia will have no spare ground forces to mount a serious threat to NATO. But even if a ceasefire is signed, Russia might struggle to divert large numbers of troops, notes Konrad Muzyka, an analyst, because that might allow Ukraine to recapture territory.

Russia, therefore, would have to build new forces. Western intelligence agencies have scrutinised how long that might take. Their conclusions vary considerably. America talks of Russia reconstituting its army “during the next decade”. Norwegian intelligence reckons five to ten years “at the earliest”. Ukraine’s estimates suggest five to seven; Germany’s are five to eight. Estonian spooks appear to be the least sanguine, offering a three-to-five year timeline for Russia to build new formations, depending on the course of the war, Russia’s economy and whether sanctions remain.

These timelines hinge on a variety of factors. Russia is churning out munitions at extraordinary speed—more than 1,400 Iskander ballistic missiles per year, as well as 500 Kh-101 cruise missiles, according to Ukrainian estimates and a recent report by the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), a think-tank in London. But in other areas, current production rates are unsustainable. Just 10-15% of the 1,500-2,000 tanks and 3,000 other armoured fighting vehicles being produced annually are new, notes RUSI. The rest are refurbished from old Soviet stockpiles. These could run dry by 2026 if present loss rates continue, notes Dara Massicot of the Carnegie Endowment. Russian armour production might have peaked this year, says Mr Muzyka.

Manpower is also a serious constraint. In the short term, Russia is recruiting some 30,000 men a month, but over the longer run it faces challenges from a declining and ageing population.

More important is the quality of these forces. “Materiel recovery will be much faster and easier than the actual ability to employ the force,” argues Michael Kofman, also of the Carnegie Endowment. Russia’s armed forces have improved dramatically in some areas, he says, such as finding and striking targets using drones, but their ability to scale this up is limited by the quality of troops, officers and staff work.

The men in the foxholes

The quality of Russia’s forces has been hurt by grievous losses. Western officials reckon since late 2024, Russian military hospitals have been operating at maximum capacity. General Chris Cavoli, NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander Europe, said in April that Russia had suffered an estimated 790,000 casualties. Many of those who have been killed or wounded are the junior officers needed to lead units in an expanded force. Public funeral notices suggest that between 2022 and 2024 Russia lost about as many lieutenants as would normally be needed to staff ten divisions or brigades, writes Ms Massicot.

A recent study by the RAND Corporation, an American think-tank, explores the different ways Russia could rebuild its armed forces. For many years before the invasion of Ukraine, Russian leaders sought to build a leaner, more professional force that relied on technology and agility. That model is now in the dustbin. Russia is reverting to an older, cruder way of war: “The centrepiece of these reforms is not innovation and technological adaptation. Rather, it is a return to mass and firepower.”

Russia’s ability to sustain a military build-up is also constrained by its struggling economy. Last year it spent 6.7% of GDP on defence, according to official figures, with spending forecast to rise this year. Yet not all of this money will be used to buy new equipment, since the figure includes payments to injured soldiers and the families of those who have been killed, as well as large salaries to entice people to sign up as contract soldiers.

The slog of war

One camp therefore argues that the threat from Russia, though real, is more manageable than commonly thought. The new formations, such as the 44th Army Corps destined for the Finnish border, are “Potemkin units”, says John Foreman, who served as Britain’s defence attaché in Kyiv and Moscow. In the latter post, he recalls, Russia claimed that it had 1m men under arms; the true figure at the time was 880,000.

Moreover, the accession of Sweden and Finland to NATO has drastically worsened Russia’s position in NATO’s north. The idea that Russia could extricate itself from Ukraine, reform its army and “march on Warsaw” is “an absolute fantasy”, concludes Mr Foreman. He doubts that Russia has any intention to attack, in any case.

Another school of thought retorts that Russia’s ability to wage war depends very much on the sort of war being waged. “In the medium term, Russia is unlikely to be able to build up the capabilities needed for a large-scale conventional war against NATO,” acknowledges Lithuania’s defence intelligence agency. “However, Russia may develop military capabilities sufficient to launch a limited military action against one or several NATO countries.” Danish intelligence sounds a similar warning: it would take five years for Russia to be ready for a big war (not involving America). But it would take only two years to prepare for a “regional war” against several countries in the Baltic-sea area, and a paltry six months to be able to fight a “local war” against a single neighbouring country.

Russia could shift 50,000 troops from Ukraine to its Leningrad military district with a minimal impact on the current war, argues Hanno Pevkur, Estonia’s defence minister. “But this would significantly change the force posture of the Russian army close to Estonia,” he warns. “To have a localised small conflict, they don’t need to have all the troops available from Ukraine.”

There are big caveats to these scenarios. The Danes assume that NATO would not rearm “at the same pace”, a premise that looks shakier today as European NATO allies, spooked by Mr Trump’s assault on them, pour money into their armed forces. The more important assumption is that Russia could keep a war localised in the first place. NATO currently deploys a string of “forward” battlegroups in eight countries, from Estonia down to Bulgaria, involving troops from 28 separate countries. American troops are present in at least three of them. Increasingly NATO is also “shadowing” Russian exercises, ensuring that it monitors and matches surges of Russian troops near the border; the “Zapad” exercise in Russia and Belarus later this year will be watched closely.

In order to fight a limited conflict, Russia would have to assume either that these forces would stand by or pull back—or, at least, that America would not step in (an assumption that would be strengthened were America to be distracted elsewhere, for instance by a Chinese attempt to invade or blockade Taiwan). That would certainly even up the odds.

Our calculations suggest that, even after adjusting for Russia’s lower wages and costs and its increased budgets, Mr Putin’s defence spending does not match that of NATO’s European members. Yet fragmentation and duplication mean that at least some of Europe’s spending is wasted. More importantly, although European forces are well armed on paper, they would struggle to target their long-range weapons, organise complex air operations, command big formations and defeat Russian air defences without American involvement. Poland, for instance, has oodles of long-range rocket launchers. But it does not have the means to find targets for them far behind the front lines. For now, most European countries are operating on the assumption that America, even under Mr Trump, will keep up that support for long enough for Europe to fill in the gaps over time—a managed transition rather than a disorderly withdrawal.

Looking for a soft flank

If that assumption holds, and if European rearmament gains pace—both big ifs—Russia is likely to remain deterred from taking any acts of war that would trigger NATO’s Article 5 mutual-defence clause. But its appetite for risk could nonetheless grow, not least if it judges that Mr Trump might overlook smaller transgressions. “Russia will gradually become more willing to use military force in the coming years to put pressure on or challenge NATO as a whole or individual NATO countries,” argues Danish intelligence.

That could involve relatively minor incidents, such as the reckless decision to interfere with American, British and French surveillance aircraft in recent years. But it could also entail more ambitious efforts to destabilise what Russia views as peripheral territory, such as the Norwegian island of Svalbard, where it might be harder to gain a consensus among NATO allies on a timely response. Non-nato states would also be easier prey still. “If you saw Russian troops from Transnistria moving into some part of Moldova,” says one intelligence insider, “I think that would be a very, very difficult contingency to deal with, and it would split nato.”

Predicting future wars is always fraught. During the cold war, America and the Soviet Union habitually misunderstood both the intentions and capability of the other. In “Watching the Bear”, a collection of essays published by the CIA in 1991, Raymond Garthoff, a former CIA analyst, reflected on the tendency, in the 1950s and 1960s, and again in the 1970s and 1980s, “to impute offensive intentions to increasing Soviet strategic offensive capabilities”. Soviet thinking, in turn, he notes, was marked by “considerable exaggerations of Western bellicosity and capabilities, including planning for initiation of war”.

But understating the risks is also dangerous. The chances of a big war near Sweden remain low, says the country’s spy agency. However, a “limited armed attack” against a Baltic state or NATO ships is entirely possible, it warns. “Such action could seem disadvantageous from a Swedish perspective,” explain the spies, “but it is important to emphasise that the Russian leadership makes decisions based on its own logic and assessment.” ■

https://www.economist.com/briefing/2025/05/08/would-vladimir-putin-attack-nato

The Economist, 8 mai

From bear to bare : Russia’s military parades have become a sign of weakness

Will this year’s event buck the trend?

Full text:

ON MAY 9th Russia will mark 80 years since Nazi Germany’s defeat in the second world war. President Vladimir Putin has invited dozens of foreign leaders to Moscow for the annual military parade, including China’s Xi Jinping and Brazil’s Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Victory Day, long a patriotic staple in Russia, has become central to Mr Putin’s efforts to shore up his regime and justify his war in Ukraine, which he has mendaciously framed as a fight against “a neo-Nazi regime”. Russia called for a ceasefire from May 8th to 11th, a move Ukraine dismissed as an attempt to calm jittery guests. The parades are meant to signal might—with rows of tanks, missiles and saluting troops.

Yet recent parades have underwhelmed. The Conflict Intelligence Team (CIT), an independent group specialising in open-source intelligence (OSINT) in Russia, has tracked parades in 57 cities over the past four years. Since the invasion of Ukraine, much of Russia’s hardware has been sent to the front—and perhaps destroyed there. The number of military vehicles on show fell from around 2,000 before the war to 1,275 in 2022, and just over 900 in both 2023 and 2024 (see chart 1). Tanks are an even rarer sight: 108 were paraded in 2021 but only 39 were spotted last year. Moscow’s display featured just one—a T-34 from the second world war (pictured).

Instead, the Kremlin appears to be padding out the events with lighter, more abundant kit. That has made the parades a show less of strength than of scarcity. For example, between 2023 and 2024 the number of light-armoured vehicles, such as Mine Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles (MRAPs) and Infantry Mobility Vehicles (IMVs), increased. For artillery, CIT recorded declines in self-propelled howitzers and most air-defence units (see chart 2). But towed artillery, which is generally lighter and cheaper, became more common.

Russia’s losses in Ukraine have been steep. Oryx, a Dutch OSINT project, has documented the destruction, damage or capture of some 21,550 Russian weapons systems as of May 1st. That includes around 4,000 tanks, which are expensive and hard to produce. Those figures would suggest that Russia has blown through the majority of its pre-war stockpile. Oryx has recorded fewer losses on Ukraine’s side: 8,805 items, including 1,167 tanks (see chart 3).

Faced with shortages, Russia has cranked up production. Factories are churning out munitions. Output of high-precision 9M723 ballistic missiles rose from around 250 in 2023 to more than 700 in 2024, according to RUSI, a think-tank. Tank plants are also busy, albeit mainly refurbishing old Soviet models—a cheaper way to bolster firepower than building modern ones. (RUSI estimates that just 10-15% of the 2,000 tanks delivered every year are new.) Some European officials worry the extra production is not just to bolster Russian forces in Ukraine but also to prepare for another war deeper into Europe.

Keen to impress, the Kremlin has promised that this year’s parade will be the grandest yet. Whatever the state of Russia’s arsenal, Mr Putin will want to put on a show.■

The Wall Street Journal, 7 mai

What Trump Fails to Understand About Putin

Russia’s dictator, steeped in myth, couldn’t care less that ‘too many people are dying’ in Ukraine.

Full text:

The ugly truth is at last dawning on the White House—or let’s hope it is—that Vladimir Putin has no interest in settling for a tie in Ukraine. The administration has spent weeks lamenting the pointlessness of the war. “Stop the killing” and “stop the bloodshed,” President Trump has said repeatedly to the combatants in press gaggles and on social media.

The phrases, coming from him, sound disingenuous. They would sound credible if Mr. Trump were a typical Western liberal who believes killing and bloodshed happen mainly when people fail to appreciate the benefits of stability and prosperity. But Mr. Trump doesn’t think that way and never has, which is why he also doesn’t offer similar laments over the bloodshed happening in Haiti, Myanmar, Nigeria, Somalia, Sudan and other places.

The Russian army’s refusal to stop launching attacks on Ukrainian civilians, Mr. Trump pronounced on April 26, “makes me think that maybe he”—Mr. Putin—“doesn’t want to stop the war, he’s just tapping me along.” Plainly Mr. Trump knows his Russian counterpart is a one-eyed jack, but he concluded that statement with another seemingly credulous appeal to liberal values: “Too many people are dying!!!”

Mr. Trump understands cutthroat opportunism, but not honor-based savagery. The people advising him—notably the real estate investor Steve Witkoff and Vice President JD Vance—seem to take Mr. Putin for a crafty Western-style pol angling for pecuniary and political advantage.

That is precisely what he isn’t. As Gary Saul Morson explained in a superb 2023 essay, “Do Russians Worship War?,” Mr. Putin fully embraces the centuries-old myth of Russia as the victim of betrayal and exploitation. The Mongols in the 13th century, the Turks in the 18th, the British and the French in the 19th, Germany in the 20th—always, in minds like Mr. Putin’s, steeped in the myth, Russia must fight foes bent on stealing its wealth and destroying its people.

May 9, the day Nazi Germany surrendered to the Soviet Union in 1945, is, for Russians, “the most important holiday of the year, consecrated by the Russian Orthodox Church,” Mr. Morson writes. “They sense their kinship with the mystical body of the people, past and present.” War in Russia, he explains, is a kind of civic sacrament: Newlyweds frequently place flowers on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Moscow, and criticizing the military is often considered blasphemous. In American war movies, “the true heroes (or most of them) survive. By contrast, countless Russian war movies and novels feature as much death as possible. The story is not complete if anyone beside the one reporting the events survives. The more death, the greater the heroism.”

Mr. Trump’s lamentations about all the killing and destruction in Ukraine will likely have the opposite of the intended effect on Mr. Putin. That, at any rate, is a reasonable conclusion from Mr. Putin’s latest pronouncement that any agreement to end the war must include Russian control of four territories not currently under full Russian control: Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia. So after weeks of browbeating Ukrainian President Volodomyr Zelensky and portraying Mr. Putin as a reasonable man—“a straightforward guy,” as Mr. Witkoff called him in an interview with Tucker Carlson—the administration managed to extract from the Russian dictator exactly nothing. Less than nothing, actually. Mr. Putin now wants more, not less.

It is a useful exercise to ask how a government’s behavior will be perceived by readers of history a century later. If, in the end, Mr. Trump listens to Mr. Vance and Donald Trump Jr. and cuts off aid to Ukraine, the outcome will invite comparisons to the allies in 1939. I’m not referring to the Munich Agreement, which happened the previous year, but to the failure of Britain and France to support Poland, as both had pledged to do, in its courageous but doomed stand against the German Wehrmacht.

The reasons for the allies’ nonintervention seemed sound at the time. Halik Kochanski, in her book “The Eagle Unbowed” (2012), writes that Britain and France moved from “a reluctance to take any action in support of Poland that might lead to German retaliation against them” to “deluding themselves that there was nothing they could do in any case because their armed forces were not ready for war, to the final justification that there was no point in taking any action because Poland was being so rapidly overrun.” The allies’ excuses in 1939 echo in the rhetoric of Mr. Zelensky’s despisers in 2025: Russia might retaliate with nukes, NATO is too weak to fight, Ukraine can’t win.

In fairness to Britain and France, they would have had to confront Hitler in Poland with their own soldiers and airmen. Yet the disgrace is real, and every informed Briton and Frenchman knows it. America need only send weapons, not men, to Ukraine. If we can’t manage that, we will deserve the scorn of our grandchildren.

Mr. Swaim is an editorial page writer for the Journal.

The Wall Street Journal, 1 mai

Perfect vs. Good in Ukraine

In a world of optimal risk-taking, the U.S. would have called Putin’s bluff long ago.

Full text:

A lot of things might have been realistically on the table in the Ukraine negotiation if the U.S. and its European allies had been willing to supply enough force.

If Ukraine were armed and supported to take back Russian-occupied territory, Vladimir Putin would have had something to negotiate over. Had the U.S. and allies been supportive of strikes on targets inside Russia, then a counterweight would have been on the table against Ukraine’s own urgent desire to end the bombing of its cities.

Two of Mr. Putin’s observable sensitivities are Crimea and keeping insulated from the war his urban middle classes in St. Petersburg and Moscow, who can end his regime in an afternoon if they take to the streets in sufficient numbers.

The U.S. and its allies had ways to put these values at risk. Where was the concerted and well-advertised collaboration on a plan to take down Crimea’s Kerch Bridge?

Unthinkingness explains one stance heard in the peanut gallery: Cut off aid to put Ukraine in the mood to bargain. In fact, the mere possibility has been an incentive to Mr. Putin not to negotiate.

On the other side, stating a military goal without providing the means to achieve it is a formula only for self-humiliation. If Ukrainian troops backed by unstinting U.S. equipment proved inadequate to liberate Crimea and the Donbas, then what? Demand direct U.S. intervention because otherwise Moscow can say it defeated Washington no less than Kyiv?

But it wasn’t just overegged fear of Mr. Putin’s nukes. The Biden and Trump administrations recognize the many ways Mr. Putin can make their lives difficult: cyberattacks, assassinations, sabotage, threats to undersea cables and now satellites. Russia can peddle ICBM technology to North Korea, submarine technology to China, antiship missiles to Iran, etc.

Willing the ends without willing the means is the happy prerogative of the pundit through the ages. But to answer a common objection: In defense of the principle that lands shouldn’t be seized by aggression, Ukraine has fought and sacrificed for three years. The U.S. and allies have invested hundreds of billions and accepted the risks that go with it. NATO is mobilizing in ways it hasn’t in decades. In words and actions, the principle of nonaggression can continue to be supported even after a realistic armistice is signed.

But no principle is advanced by making the perfect the enemy of the good. The reality principle defines every armistice ever concluded, including the many ugly ones you’re already thinking of.

So in the current negotiation numerous military goals the U.S. was unwilling to underwrite, unsurprisingly, won’t be met. Those thundering on Twitter for Mr. Putin’s defeat exhibit the deficiencies of Twitter politics. Missing is even a microscopic whisper of the necessary democratic coalition-building. Unseen is any money and grassroots effort to rally U.S. public opinion and its representatives to a more muscular approach.

For the record, the strategic and historical motives cited for Mr. Putin’s war strike me as decidedly upstream from his immediate concern: securing his regime for his declining years. Letting Ukraine slip away might be all the justification a rival needs to remove him.

The negotiations don’t seem now on the edge of success, but a cold war would follow a hot war. Tested would be whether a westernizing Ukraine is a more successful model than the lawless kleptocracy Mr. Putin means to perpetuate into his dotage mainly for his own personal security. I know which outcome I would bet on.

Mr. Trump has a reputation for bold moves only in a relative sense: Politics makes all politicians risk-averse. They prefer small, reversible steps. They kick the can down the road whenever possible.

Mr. Putin in the war’s opening days blatantly suggested that any NATO interference would be met with a nuclear response because Mr. Putin knew he could do nothing to save his army on the roads of Ukraine if NATO sent in its F-35s. Even the Biden administration likely guessed there was a 99.99% chance Mr. Putin was bluffing. Mr. Putin would back down if NATO threatened destruction of his army—that is, if his aides hadn’t already dispatched him to Valhalla to assure the survival of their own hides.

World War III wouldn’t have happened. In every way the outcome might have bought the world another generation of deterrence, peace and stability. But no U.S. president would have taken the risk. Voters wouldn’t have supported it. For reasons explored systematically by the field of behavioral economics, humans are programmed by nature to play it safer than a clinical weighing of risks and benefits says they should.

The Wall Street Journal, 1 mai

U.S. Army Plans Massive Increase in Its Use of Drones

The shift to more small unmanned aircraft is based on lessons from Ukraine battlefield

Full text:

HOHENFELS, Germany—The U.S. Army is embarking on its largest overhaul since the end of the Cold War, with plans to equip each of its combat divisions with around 1,000 drones and to shed outmoded weapons and other equipment.

The plan, the product of more than a year of experimentation at this huge training range in Bavaria and other U.S. bases, draws heavily on lessons from the war in Ukraine, where small unmanned aircraft used in large numbers have transformed the battlefield.

The Army’s 10 active-duty divisions would shift heavily into unmanned aircraft if the plan is carried out, using them for surveillance, to move supplies and to carry out attacks.

To glean the lessons from Ukraine’s war against Russia, U.S. officers have debriefed its military personnel and consulted contractors who have worked with Kyiv’s military about their innovative use of drones.

“We’ve got to learn how to use drones, how to fight with them, how to scale them, produce them, and employ them in our fights so we can see beyond line of sight,” said Col. Donald Neal, the commander of the U.S. 2nd Cavalry Regiment. “We’ve always had drones since I’ve been in the Army, but it has been very few.”

The effort to integrate drones was on full display in February when a brigade from the 10th Mountain Division battled against a mock opponent here. During the Cold War, the huge Hohenfels training range was used to prepare for armored warfare against a potential Soviet attack on Western Europe.

But in an updated scenario reflecting new combat tactics used in Ukraine, small drones buzzed in the gray winter skies controlled by soldiers and defense contractors in the muddy fields below.

The bitter cold caused ice to form on some of the aircraft’s rotor blades and sapped the batteries, a glitch that hadn’t arisen in earlier exercises in Hawaii and Louisiana. Soldiers rushed to recharge them as they sought to keep the unmanned aircraft aloft.

Ukrainian and Russian troops have clashed with artillery, armored vehicles, manned fighters and other conventional systems. But it is drones that have transformed the conflict because they are cheap, can attack in swarms to overwhelm defenses, and can send live video feeds to the rear that can make it difficult to hide on the battlefield, analysts said.

In Ukraine and the Red Sea, drones are changing the way wars are fought. The U.S. and other countries are investing in a new way to retaliate: lasers. WSJ explains how one laser works and why the tech is so difficult to perfect. Photo: Alexandra Larkin

“Land warfare has transitioned to drone warfare. If you can be seen, you can be killed,” said Jack Keane, the retired general who served as vice chief of staff of the Army and observed the exercise here. “A soldier carrying a rocket-propelled grenade, a tank, command and control facilities, artillery position can all be taken out by drones very rapidly.”

Drones are just one capability the Army plans to field as the Army seeks to buttress its ability to deter Russia and China after decades of fighting insurgencies in the Middle East and Central Asia.

The service is also developing ways to better link soldiers on the battlefield, drawing on cellphones, tablets and internet technology, and is acquiring a new infantry squad vehicle. The Army plans to invest about $3 billion to develop better systems for shooting down enemy drones and is moving to build up its electronic warfare capabilities.

Altogether the overhaul would cost $36 billion over the next five years, officials said, which the Army would come up with by cutting some outmoded weapons and retiring other systems—steps that will require congressional support.

The “Army Transformation Initiative,” as the service’s blueprint is known, comes as Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency has been seeking to slash spending and personnel across the government.

Gen. Randy George, the Army chief of staff, and Daniel Driscoll, the secretary of the Army, met with Vice President JD Vance recently to explain that the service had a plan to upgrade its capabilities while making offsetting cuts, a Pentagon official said. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth endorsed the plan in a directive signed this week.

“We aren’t going to ask for more money,” George said in an interview. “What we want to do is spend the money that we have better.”

The Army is halting procurement of Humvees, its main utility vehicle for decades, and will no longer purchase its Joint Light Tactical Vehicle. It is also stopping procurement of the M10 light tank, which has proven heavier and less useful than planned when the program began a decade ago. It is also planning to retire some older Apache attack helicopters. A reduction in civilian personnel will also contribute to the savings.

Three brigades—the 3,000 to 5,000 soldier formations that make up divisions—have already been outfitted with some of the new unmanned systems, and the goal is to transform the rest of the active-duty force within two years, Driscoll said in an interview. A division typically has three brigades.

Army divisions that haven’t begun to incorporate the new technology typically have about a dozen long-range surveillance drones, which were first deployed more than a decade ago.

The Marines have done away with their tanks as part of a separate overhaul that calls for small missile-toting combat teams to hop from island to island in the Western Pacific to attack the Chinese fleet in a conflict.

The Army plan, which is intended to boost the service’s capabilities in Asia as well as Europe, still envisions acquiring new tanks, long-range missiles, tilt-rotor aircraft and other conventional systems.

The American industrial base will have to increase to produce the latest off-the-shelf technology that the Army wants. Last year, Ukraine built more than two million drones, often with Chinese components, U.S. officials say. But the U.S. military isn’t allowed to use parts from China.

https://www.wsj.com/politics/national-security/us-army-drones-shift-20cc5753?mod=hp_lead_pos7

The Wall Street Journal, 30 avril

Ukraine’s Crimea Lies at the Heart of Russia’s Invasion—and Trump’s Peace Plan

The military takeover of the peninsula was the first of Russia’s land grabs

Full text:

KYIV, Ukraine—One of the central points of tension in President Trump’s strained efforts to end the war in Ukraine is a Black Sea peninsula that Russian President Vladimir Putin has placed at the heart of his national project.

For over a decade, successive U.S. administrations, including Trump’s first, decried Russia’s armed seizure of Crimea in 2014 and said they would never recognize the land grab—but did little to help Kyiv get it back.

Now, Trump is publicly repudiating that stance, saying that the peninsula should become part of Russia to facilitate a peace deal to end the war. In an interview with Time published on Friday, Trump said: “Crimea will stay with Russia.”

Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky has balked at the suggestion, telling reporters that, “Ukraine will not legally recognize the occupation of Crimea.”

President Trump answered questions about his meeting with Ukrainian President Zelensky at the Vatican. Secretary of State Rubio said this week would be “very critical” in trying to end the war. Photo: Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images

Trump and Zelensky met Saturday ahead of the funeral of Pope Francis, their first face-to-face talk since an acrimonious Oval Office meeting in February. While details of the 15-minute discussion weren’t public, both sides described it as good and Trump later criticized Putin on social media, questioning whether the Russian leader wanted to stop the war.

Since taking over Crimea, Russia has clamped down on opposition and promoted a Russian vision of its history through museums, schools and the repression of dissent.

To Ukraine, and most of its allies, Russia’s takeover of Crimea was a violation of international law—and the West’s failure to strongly resist it fed Moscow’s appetite.

Initially, Russia insisted its troops weren’t present. Days after protests in Kyiv ousted a pro-Russian president in February 2014, men carrying rifles and wearing unmarked uniforms appeared outside the Russian naval base in Sevastopol.

Ukrainians protested to prevent Russians from entering the Crimean parliament but overnight, on Feb. 27, special-forces troops burst inside, hoisted a Russian flag and later supervised a vote to hold a referendum on joining Russia.

The government in Kyiv, struggling to establish a new administration and dissuaded from fighting by Washington, didn’t give clear orders to soldiers in Crimea to resist—something Trump has criticized.

The Obama administration did little to stop the takeover, expressing its displeasure, calling on Russia to de-escalate and applying sanctions on some Russian officials. Trump has blamed then-President Barack Obama for allowing Russia to take Crimea, saying it wouldn’t have happened if he were in charge.

Crimea was transferred under Ukraine’s control in 1954 when then-leader of the Soviet Union Nikita Khrushchev signed a decree that cited the economic, territorial and cultural closeness of Crimea and Ukraine. When Ukraine held an independence referendum in 1991, over half of Crimean voters cast ballots in favor.

Russia presented its so-called referendum in 2014 as a homecoming steeped in Soviet nostalgia, a choice between Russian peace and Ukrainian “Nazism,” a word it frequently uses to smear opponents. Ukrainian television and radio channels were blocked.

At first, pro-Ukrainian demonstrations continued. A day of organized protest took place on March 9, the birthday of Ukraine’s national poet Taras Shevchenko.

Then the disappearances began, recalled Olha Skrypnyk, who taught history and lived in the seaside city of Yalta. Some 20 activists, two of them Skrypnyk’s colleagues, were detained.

“They were tortured, degraded, beaten, they put cigarettes out on them, forced them to sing the Russian anthem,” said Skrypnyk, who now runs the Crimean Human Rights Group, a nongovernmental humanitarian organization.

A day before the referendum, a man’s body was found on the roadside, his head wrapped in Scotch tape and his body bearing signs of torture. He was identified as Reshat Ametov, an activist from the indigenous Crimean Tatar community who had been detained 12 days earlier.

The next day, March 16, Russians held their ballot at polling stations guarded by gunmen. Russia announced that 95.5% of Crimeans voted in favor. Putin signed a law to integrate Crimea the following day in a ceremony at the Kremlin. In a later speech, Putin would say that Crimea was Russia’s Temple Mount.

“Crimea was the base from which everything began,” said Skrypnyk, who left Crimea the day of the referendum. “That’s why the takeover of Crimea was only the first step toward the full-scale invasion. Russia was not going to stop.”

Russia swiftly began working to erase any trace of Ukraine in Crimea and stamp its own imprimatur, including by looting museums and destroying historical sites. As Russia increased its navy and army presence, families also flooded in. Newly launched government programs lured civilians into relocating in a bid to reshape the population.

By Ukraine’s estimates, about 800,000 Russians moved to the peninsula after the occupation, while at least 53,000 Ukrainian citizens left. The population before the takeover stood at 2.3 million, according to Ukrainian government figures.

The new authorities forced Russian passports on Ukrainian citizens, even when they were unwanted. Declining a passport meant losing access to healthcare, schools, work and pensions. Ukrainian passport holders were constantly harassed.

“To renounce the citizenship of the Russian Federation, you need to make an appeal to Putin,” said Olha Kuryshko, the Ukrainian president’s representative for Crimea. Most forego this step, fearing persecution.

Russia established its own court system and relocated judges from the mainland to hold what Ukrainian authorities and human-rights experts denounce as illegitimate criminal proceedings targeting anyone Russian authorities deemed a threat, particularly activists and journalists. The repression was so vast that Russia opened additional detention facilities.

Crackdowns hit particularly hard the Crimean Tatars, who had been deported en masse under Stalin and only began returning when the Soviet Union repression softened in the 1980s.

“Occupation authorities constantly monitor pro-Ukrainian people and try to choke off any resistance movement and any freedom of speech,” said Viktoria Nesterenko, who heads Crimea monitoring for the human-rights watchdog Zmina. “This means they’re very afraid of these people.”

Youth summer camps became places of ideological re-education. Children learned how to handle weapons and throw grenades. The Russian authorities’ stated goal was to raise citizens ready to serve in the Russian army.

The jewel in Putin’s Crimean crown was a bridge across the Kerch Strait linking the peninsula to the Russian mainland, which took two years to build. When the bridge opened in 2018, Putin drove across it in a truck.

As it prepared for the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia bolstered its forces in Crimea, using it as a launchpad for occupying the southern Ukrainian regions of Zaporizhzhia and Kherson.

Tanks rolled in from the peninsula to the mainland. Russia’s Black Sea fleet pummeled the Ukrainian coastline.

After Ukrainian territories were occupied in 2022, the peninsula acted as a logistics hub supporting the Russian army. Ukrainian missile and drone attacks were frequent, and the Kerch bridge was twice struck and had to be closed.

Russia used the port in Sevastopol to ship stolen grain out and prisons inside Crimea to keep newly detained Ukrainians in. Many of the thousands of children taken from Ukraine by occupation authorities were placed in Crimean camps.

Russia began cracking down more brutally on pro-Ukrainian sentiment. Since 2022, it has seized twice as many properties as in the eight years prior. Human-rights organizations say women and the elderly are increasingly targeted.

Because most of those detained are civilians, there are no mechanisms for prisoner exchanges. Authorities say 10 people from Crimea have been exchanged since 2014.

One of them is Leniye Umerova, a Crimean Tatar born in the region who moved away as a teenager after witnessing the occupation. At the end of 2022, she learned that her father was hospitalized and decided to visit him in Crimea, fearing not having said goodbye.

She traveled into Russia via the Caucasus republic of Georgia, where a Russian border guard asked her why she had a Ukrainian passport rather than a Russian one, given that her place of birth was listed as Crimea.

“I told him I didn’t want one,” Umerova said.

The Russians detained Umerova for over a year and a half, moving her around various prisons before charging her with espionage. She was exchanged back to Ukraine last fall. For Umerova, the suggestion that Crimea will be recognized as Russian sparks anger and indignation.

“I, as a Crimean, do not agree with this,” she said. “We cannot give up Crimea.”

Zelensky agrees, and has pushed back on the idea of Ukraine giving up the peninsula. He appended to a social media message a 2018 Crimea Declaration by Trump’s then-secretary of state, Mike Pompeo.

Russia, he wrote, “sought to undermine a bedrock international principle shared by democratic states: that no country can change the borders of another by force,” Pompeo said in the declaration.

Days earlier, Trump had been more ambiguous.

“What will happen with Crimea from this point on?” he said at a news conference. “That I can’t tell you.”

The Wall Street Journal, 29 avril

Trump Can Make Russia Pay for Peace in Ukraine

As Moscow lets the war drag on, Washington should step up the pressure, including sanctions, on the beleaguered Russian economy.

Full text:

Russia wants the Ukrainian peace talks to fail and the U.S. to cut off aid to Ukraine and walk away. President Trump finally appears to understand Vladimir Putin’s thinking, musing on Truth Social that “maybe he doesn’t want to stop the war, he’s just tapping me along.” That is exactly what Mr. Putin is doing. If the Trump administration wants a Ukraine deal, it must raise the costs on Russia.

Moscow’s negotiating strategy in Ukraine is similar to the strategy it adopted during the Syrian war: drag out the peace talks, wait for the other side to become so frustrated with diplomacy that its leaders walk away, and ramp up the war. The Taliban successfully used the same strategy in Afghanistan with the Biden administration. But Moscow doesn’t hold all, or even most, of the cards. It has at least two vulnerabilities that Mr. Trump can exploit.

The first is Russia’s economy, which Mr. Trump hinted at when he suggested in the same online post that Russia could “be dealt with differently, through ‘Banking’ or ‘Secondary Sanctions.’ ” Russia is grappling with inflation, labor shortages, brain drain and limited paths to economic growth. The country’s economy is perilously exposed in oil and gas, which make up between 30% and 50% of Russia’s total federal budget revenue.

Increased sanctions against Russia’s energy sector would likely cause significant pain. Energy sanctions could be combined with sanctions against other Russian exports, such as minerals, metals, agricultural goods and fertilizers. Some members of Congress, led by Sens. Lindsey Graham (R., S.C.) and Richard Blumenthal (D., Conn.), have suggested putting massive tariffs on imported goods from countries that buy Russian oil, gas, uranium and other products.

A second Russian vulnerability is the blood cost of a protracted war. The Russian military has performed dreadfully on the battlefield since it began its current offensive last year. Russian ground forces have taken only a tiny amount of Ukrainian territory in the past year, mostly in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Russia’s average rate of advance has been slower than the most grueling battles of World War I, including the Franco-British offensive during the 1916 Battle of the Somme, according to estimates by the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Even worse for Moscow, its soldiers have died in extraordinary numbers. Since February 2022, Russia has likely sustained more than 900,000 total casualties, including more than 172,000 killed. Russia will soon pass the threshold of one million total casualties. CSIS estimates Moscow has lost more than three times as many soldiers in Ukraine as in all Russian and Soviet wars combined between the end of World War II and February 2022.

If Moscow continues to drag its feet, a U.S. decision to provide more weapons, intelligence and training to Ukraine would escalate Russia’s battlefield costs. U.S. Army Tactical Missile Systems, High Mobility Rocket Systems and other weapons systems and intelligence assistance have been devastating to Russia. And unlike the forever wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the U.S. has lost no soldiers in Ukraine. American military assistance has also benefited workers in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas and other states who are making the weapons systems.

Yet despite Russia’s vulnerabilities, the U.S. has failed to wield either the economic or military cudgel. Without actual pain, Mr. Putin will drag the talks out, keep fighting and wait for the U.S. to walk away.

The U.S. abandoning Ukraine would dramatically tilt the balance of power in favor of Russia and its allies—China, Iran and North Korea. China has provided Russia with military aid including computer chips, advanced software, drones and even Chinese mercenaries. Iran has supplied drones, artillery shells, ammunition and short-range ballistic missiles. North Korea has sent soldiers, artillery rounds, rockets, short-range ballistic missiles and other munitions.

These countries are also cooperating in other regions. Russia has supplied weapons and intelligence to the Houthis, an Iranian-backed terrorist group based in Yemen that is conducting attacks against the U.S. Navy, commercial ships and Israel. China recently provided satellite imagery to the Houthis for attacks.

Senior Japanese, South Korean and Taiwanese government officials tell me that a Russian military victory in Ukraine would embolden China and North Korea in Asia. It also would signal American weakness. There is far too much at stake in Ukraine for the U.S. to walk away.

America holds most of the cards here. It needs to start playing them.

Mr. Jones is president of the defense and security department at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

The Economist, 28 avril

The kopek drops : Vladimir Putin’s money machine is sputtering

After years of resilience, Russia’s economy is slowing down

Full text:

FROM KALININGRAD to Vladivostok, something has changed. A high-frequency index produced by Goldman Sachs, a bank, suggests that, since the end of last year, Russia’s annualised economic growth has fallen from around 5% to around zero (see chart). VEB, the Russian development bank, finds similar trends in its estimate of monthly growth. A high-frequency measure of business turnover compiled by Sberbank, Russia’s largest lender, has dipped. Although more circumspect, the government acknowledges that something is up. In early April the central bank noted that recently “a number of sectors recorded lower output because of plummeting…demand”.

Russia’s worries come after three years in which its economy outperformed almost all forecasts, owing to the combination of a fiscal splurge, high commodity prices and the militarisation of the economy. Following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, economists predicted a contraction in annual GDP of up to 15%. In the event, GDP fell by 1.4% that year, before expanding by 4.1% in 2023 and 4.3% in 2024. Consumer confidence neared record highs. As it started to seem that Donald Trump, America’s president, might give Vladimir Putin what he wants to end his war on Ukraine, some expected Russia’s economy to accelerate even further in 2025.

What is behind the sudden slowdown? Three explanations stand out. The first relates to what Russia’s central bank euphemistically calls the “structural transformation” of the economy. Having previously faced towards the West and accepted private enterprise (within limits), it has since 2022 become a war economy that faces the East. This transformation has required vast investment, not only in weapon and ammunition factories but also in new supply chains enabling more trade with China and India (as well as more production at home). By the middle of 2024 real spending on fixed capital was 23% higher than in late 2021.

That adjustment, says the central bank, is now complete. Military expenditure is following a similar pattern. Julian Cooper of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, a think-tank, estimates that this year military spending will grow by just 3.4% in real terms, a screeching slowdown from the 53% increase of last year. Weaker spending on “structural transformation” means slower growth—but that should not worry Mr Putin if it frees up investment for productive uses. “As strange as it may sound, given the macroeconomic realities, we don’t need such growth yet,” he said in December.

The second factor is monetary policy. Russian inflation has been above the central bank’s target of 4% year on year for months, even surpassing 10% in February and March. Gung-ho military spending is one cause, but so is a shortage of labour caused by conscription and the emigration of skilled workers. Last year nominal wages rose by 18%, forcing companies to put their prices up. In response the central bank has tightened the screws. On April 25th it opted to keep its benchmark interest rate at a punishing 21%, its highest level since the early 2000s.

Its super-hawkish stance may finally be paying off. High rates have encouraged capital to flow into the rouble; a stronger currency, in turn, makes imports cheaper. Russians’ expectations for inflation over the next 12 months are softening, from a recent peak of about 14% to around 13%. High-frequency data suggest that inflation is edging down. The flipside of disinflation is slower growth. Rather than spending it, Russians are putting their money into savings accounts. High rates further discourage capital investment.

Were that the whole story, perhaps Mr Putin would remain content. For Russia’s government, a small, gradual deceleration may be a price worth paying if that means taming inflation. The problem is that the slowdown is neither gradual nor small. This is because, in recent weeks, a third factor has come to dominate all others—external conditions have soured. As America’s trade war has escalated, global growth forecasts have plunged, and oil prices have followed. Economists are particularly concerned about China, the largest buyer of Russian oil. The IMF has cut its expectations of Chinese GDP growth in 2025 from 4.6% to 4%.

Falling oil prices are causing Russia all sorts of trouble. They have hit the stockmarket, where oil companies account for a quarter of capitalisation. The MOEX index, which tracks the share price of the top 50-odd listed firms, is down by a tenth from its recent peak. As export receipts decline, sliding oil prices directly affect the real economy, too. Already the government’s coffers are feeling the pinch: in March oil-and-gas tax revenue fell by 17% year on year. And on April 22nd Reuters reported, citing official documents, that the government is expecting a sharp slowdown in oil-and-gas sales this year. Mr Trump may be well disposed towards Mr Putin, but with his trade war he has kicked him in the teeth. ■

The Economist, 28 avril

Hard pounding : Ukraine’s fighters fear Russian attacks and Trump’s ceasefire

On the front line they want peace but not at any price

Full text:

“THE DARKEST moment of this war is now,” says a Ukrainian intelligence officer. Along roads in the east tank transporters lumber towards the front line while ambulances speed away from it. In the past few weeks the Russians have ramped up drone and missile attacks on Ukrainian cities, their soldiers are mounting a renewed offensive aimed at creating a breakthrough in the east and Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukraine’s president, is coming under intense American pressure to sign up to a peace plan that looks much more favourable to Russia than to Ukraine. On April 25th Donald Trump’s envoy, Steve Witkoff, met Vladimir Putin in Moscow for talks that Mr Trump later described as having reached agreement on “most of the major points”. The president called for a meeting between Ukraine and Russia “at very high levels, to ‘finish it off.’” But there is no indication that Ukraine is ready to approve the American proposals.

The monumental road sign that welcomes people to Donetsk province, roughly two-thirds of which is occupied by Russia, has become a shrine to the region’s war dead, festooned with military flags and protected by an anti-drone net. Cigarettes have been left as offerings for fallen comrades. But it is a sign of the times that the road beyond has been closed in the last few weeks, and a back-road diversion opened, because the route skirting the besieged city of Pokrovsk has now become too dangerous.

The leaked American ceasefire proposal would end sanctions on Russia, freeze the front line and see America formally recognise Russia’s annexation of Crimea. The intelligence officer, based in Kyiv, does not hide his disdain. “No one who has any shred of dignity would sign this,” he says. Ukraine’s political and military leadership are solidly behind Mr Zelensky, he says. Mr Trump wants a success to proclaim for his 100th day in office, on April 29th, and Vladimir Putin has ramped up his military offensive because he wants a victory to crown Russia’s celebrations on May 9th, the 80th anniversary of the end of the second world war, he believes. But both men “will break their teeth” on Ukrainian resistance, he says.

On the front, though, the language is far less gung-ho. Soldiers are focused on killing Russians and staying alive rather than on high politics. They report that in the past month there has been a major upsurge in fighting, especially in the area south of the town of Kostiantynivka. Ukrainian forces have driven the Russians back at some points, but more territory has been lost than regained. Russia has been able to increase attacks thanks to the redeployment of troops from its Kursk region, where it has recently driven out Ukrainian forces. But only a few of them in turn have been freed up to fight in the east. They are now locked down defending the Sumy region, over the border from Kursk, which the Russians are also now attacking.

A command bunker of the 91st Anti-Tank Battalion lies in a former nuclear shelter underneath a bombed-out factory in a town we have been asked not to name. Large military tents have been erected here to serve as dormitories, and the nerve centre of the operation is a set of rooms with banks of screens and laptops. “Motherfuckers,” exclaims “Sheriff”, the commanding officer, as, via a surveillance drone, he sees two Russian soldiers scurrying along a road hauling a mortar tube in the village of Kalynove, which they captured on April 11th. Sheriff says that in his sector the Russians have stepped up pressure with the 21st century equivalent of cavalry charges. In one of them 100 Russians on 50 motorcycles charged Ukrainian positions. Trying to stop them is like being in a shooting gallery, he says.

According to the intelligence officer this matches what Ukrainian troops have noticed elsewhere, as pressure in the east increases. Russian forces are concentrating huge numbers of men to capture specific targets. Although up to 80% of those troops “are doomed”, the sheer numbers thrown into the assault mean that some will get through. As Ukraine does not have enough soldiers to counter them it is slowly losing ground. Sheriff says he wants a ceasefire to come into effect, not to preserve territory but “to save lives”.

“Craft”, the deputy commander of a National Guard battalion, says his men near Ocheretyne now find themselves fighting an area overlooked by high ground taken by the Russians in a pocket south of Kostiantynivka, and he believes that they may soon have to regroup. That would not be a retreat, he says, but a way to position his men to kill more Russians. But Russians would celebrate such a pullback as a victory, as it would mean that Kostiantynivka was in danger of falling. If it did, the road would be opened to advances towards more important towns in Donbas.

Toretsk, one of the towns in the pocket, has all but fallen. Ivan, a soldier deployed to the front there but relaxing for a few hours in the nearby town of Druzhkivka, says that in his sector the main thrust of the Russian attack had come in the form of glide bombs and drones. But these are not the Ukrainians’ only problem. For a fortnight he and his colleagues have been trying to help five colleagues living under the rubble of a ruined house. They are marooned 2.5km beyond the newly pulled-back Ukrainian front line, and are only 70 metres from the nearest Russian position, which Ivan and his men are bombing.

They have been using drones to drop food, water and batteries to the trapped men, but can’t find a way to rescue them in territory where other drones can kill anyone seen moving. There was no ceasefire here on Easter Sunday, when Mr Putin declared one, and the risk of summary execution made surrendering too risky. The men are disoriented and wounded and asking how they can be rescued. “Psychologically it is very hard.” Ivan says. “No one understands what is happening here.” ■

Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 27 avril

Putins treuherziger Freund: Steve Witkoff vermittelt mit fragwürdigen Folgen

Donald Trump vertraut die kniffligsten Fragen der Weltpolitik seinem persönlichen Freund an. Der Immobilienmogul Witkoff verzichtet auf Fachkenntnis und vertraut auf seine Intuition. Wladimir Putin kann das nur recht sein.

Full text:

Diesmal war alles offiziell und fast wie aus dem Lehrbuch der Diplomatie. Fernsehkameras hielten den Moment fest, als der Sondergesandte des amerikanischen Präsidenten Donald Trump, Steve Witkoff, den ovalen Saal im Senatspalast des Kremls betrat, von Präsident Wladimir Putin wie ein alter Freund begrüsst wurde und am Verhandlungstisch Platz nahm.

Neben Witkoff setzte sich nur eine Dolmetscherin, Putin liess sich von seinem aussenpolitischen Berater Juri Uschakow und seinem Sonderbeauftragten für russisch-amerikanische Wirtschaftszusammenarbeit, Kirill Dmitrijew, begleiten. Noch nie hatte der Kreml so viel Einblick in die Gespräche mit Trumps Unterhändler gegeben. Das entsprach den Erwartungen an das Treffen und der damit verknüpften Frage, ob Trumps «Friedensplan» der Durchbruch in Moskau gelinge. Aber wie immer bei Witkoffs Unterredungen wurde zunächst nur wenig bekanntgegeben. Es sei unter anderem um die Möglichkeit gegangen, den direkten Dialog zwischen Russland und der Ukraine wieder aufzunehmen, sagte Uschakow. Man sei sich näher gekommen.

Die Stimme des Präsidenten

Witkoff ist kein gewöhnlicher Unterhändler. Diplomatische Erfahrung besitzt er keine, von Russland und der Ukraine hat er wenig Ahnung. Er reist an, als wäre er ein Privatmann und kein Vertreter einer Grossmacht – im Privatflugzeug, das er angeblich selbst bezahlt. Sein Stab im Aussenministerium ist klein und weiss, wie der amerikanische Fernsehsender CNN berichtet, oft nicht genau, was sein Chef gerade tut. Witkoffs Büro befindet sich im Weissen Haus, im Oval Office ist er fast täglich.

Der Rechtsanwalt, der zum Immobilienmogul in New York und zum engen Vertrauten Trumps wurde, verkörpert den neuen Stil in Washington, der mit alten Gepflogenheiten bricht. Er kommt von aussen, ohne den Stallgeruch der Diplomatie und der Denkfabriken. Fachberater, wie sie in der amerikanischen Administration über Jahrzehnte im Umgang mit der Sowjetunion und später Russland üblich waren, fehlen an seiner Seite – und das, obwohl er sich gleichzeitig mit dem Ukraine-Krieg, dem Nahostkonflikt und Iran befasst. Er handelt mit der Intuition eines Geschäftsmanns und ist «his master’s voice». Offenbar schätzen das seine Gesprächspartner: Er gibt ihnen das Gefühl, direkt mit Trump zu sprechen.

Für seine Vermittlungstätigkeit ist das nicht unproblematisch. Die persönliche Note, mit der er zu verhandeln scheint, mag charmant, mitunter auch effektiv sein. Aber am Beispiel der Gespräche über ein Ende des Ukraine-Krieges zeigt sich, zu welch verzerrter Wahrnehmung fehlende Distanz, der Mangel an tiefgründigem Wissen und an Erfahrung im Umgang mit hartgesottenen Diplomaten und Geheimdienstfunktionären führen.

Verbreitung russischer Narrative

Witkoffs Russland-Abenteuer begann Mitte Februar mit der geheimen Mission, einen Gefangenenaustausch zu organisieren und darüber Vertrauen zum Kremlchef aufzubauen. Die Aufgabe gelang ihm. Dem berufsbedingt geschickten Menschenfänger Putin gelang es umgekehrt, den politisch unbefleckten Immobilienunternehmer in stundenlangen Gesprächen für sich und die russische Sicht auf die Ukraine einzunehmen. Mit Kirill Dmitrijew stellte er ihm zudem einen in Amerika ausgebildeten Finanzfachmann gegenüber, der sich für Russland Witkoffs und Trumps Geschäftssinn zunutze machen soll. Es habe sich Freundschaft entwickelt, sagte Witkoff später in einem seiner regelmässigen Fernsehinterviews, in denen er geradezu treuherzig seiner Bewunderung für Putin Ausdruck verleiht.

Witkoff berichtete freimütig davon, wie ergriffen er gewesen sei, als Putin ihm erzählt habe, wie er nach dem Attentat auf Trump in seiner Hauskapelle für den Freund gebetet habe. Auch die Geschichte von dem Porträt von Trump, das der Kreml bei einem seiner Hofmaler in Auftrag gegeben hatte, wäre ohne Witkoff kaum bekanntgeworden. Es zeigt Trump in der Pose kurz nach dem Attentat, vor dem Hintergrund New Yorks mit der Freiheitsstatue und einer grossen amerikanischen Flagge (der eine Sternenreihe fehlt).

Entscheidender als Witkoffs Stolz über seine angebliche Freundschaft zum russischen wie zum amerikanischen Präsidenten sind die politischen Folgen dieser Laien-Diplomatie. Witkoff biedert sich Putin an und reiste bis jetzt vier Mal nach Russland. In Kiew war er in der Zeit nie. In Interviews, besonders in jenem mit dem Fernsehmoderator Tucker Carlson im März, legte er offen, wie er russische Narrative übernimmt und wie wenig er über die sowjetische, russische und ukrainische Geschichte weiss. Er meinte unter anderem, Putin gehe es vor allem um die vier besetzten Gebiete plus Krim, und suggerierte später offenbar gegenüber Trump, der einfachste Weg zum Frieden wäre es, wenn die Ukraine diese von Russland beanspruchten Territorien abgäbe.

Diese seien «russischsprachig», und die Bürger hätten in Abstimmungen für die Zugehörigkeit zu Russland votiert, sagte er zu Carlson. Im Gespräch mit diesem konnte er die Namen der Regionen nicht korrekt nennen und behauptete fälschlich, der sowjetische Führer Nikita Chruschtschow habe den Donbass, Saporischja und Cherson der Ukraine zugeschlagen. Letzteres zeugt nur von Unwissenheit, die Behauptung zu den Resultaten der illegalen Referenden jedoch entspricht der russischen Propaganda, ebenso wie Trumps jüngste Äusserungen zur Krim, welche die Ukraine «ohne jeden Schuss» Russland überlassen habe.

Russland nutzt Witkoff aus

Witkoffs Diplomatie der Improvisation lässt kein Verständnis für das grössere Ganze erkennen. Die Folgen eines «Deals» mit Russland, der in der Ukraine vorläufig die Waffen zum Schweigen bringt, aber mit der Anerkennung der hinterlistigen Krim-Annexion und der Reinwaschung des Aggressors die Sicherheitsinteressen Europas ignoriert, scheinen ihn nicht zu interessieren. Witkoff betreibt das Geschäft für seinen Chef, dem es in erster Linie um den eigenen Erfolg als «Friedenspräsident» geht.

Auch Russland kommt die Witkoffsche Diplomatie-Imitation zupass: Gelingt es, wenigstens einen fragilen «Frieden» herzustellen und dabei die Ukraine nachhaltig auch politisch und militärisch geschwächt zu belassen, feiert sich Putin mit Trump als Friedensbringer und hofft auf die Dividenden eines neu geordneten Grossmächteverhältnisses.

The Wall Street Journal, 26 avril

Schlock Art of the Ukraine Peace Deal

Behind closed doors, self-interest rules. So the possibility of success hasn’t yet been foreclosed.

Full text:

I always guessed the “Art of the Deal” author would eventually suggest that Russia buy Crimea from Ukraine to legalize its 2014 seizure of the strategic peninsula. Put aside Vladimir Putin’s airy fairy rumination on the mystical unity of Ukrainians and Russians. As he admitted days before the current invasion, a practical problem bedeviled Mr. Putin. If a Ukraine drawing closer to the West tried to reclaim Crimea, would Russia be at war with NATO?

The U.S. never put the chips on the table seriously to threaten Russia’s hold on Crimea, but it still owns a giant and valuable carrot in being able to offer, as a result of negotiation, a path to legalize that hold. One analysis, by the Jamestown Foundation, mentions a figure of $40 billion.

But instead the Trump administration this week asks Ukraine simply to concede Crimea, which Ukraine promptly rejected.

The administration now intends to “walk away” if the “process” doesn’t bear fruit, claims JD Vance. Meaning what? President Trump can retreat from his stance as neutral “mediator,” adopted (a tad unrealistically) for the talks. He would find it harder to disown a decade-old U.S. role (which really took off under his first presidency) as Ukraine’s prime military ally and supplier.

In a negotiation, outsiders see what the parties decide to show. Therefore commentators are at especially high risk of making fools of themselves by opining officiously on what’s happening behind closed doors. Even more so if they gamely assume the Trump administration is competent. Still, a few things can be said:

Mr. Putin needs a deal (of a certain kind) but must carefully exhibit that he doesn’t. Mr. Trump wants a deal not only for the glory of Trump but to avoid the risk of having to choose between abandoning Ukraine and digging the U.S. deeper into the war.

Ukraine obviously stands to benefit by no longer being subjected to Russian attacks. Also plainly, Ukraine’s leaders would be fools, and President Volodymyr Zelensky is not a fool, to make it easy on the U.S. to satisfy its own aims in the war at the cost of Ukraine’s aims. Ukraine has leverage, contrary to Mr. Trump’s insistence that it lacks cards. In fact, it has big domestic U.S. political cards. That’s one reason Kyiv and not Moscow has been the recurrent target of Mr. Trump’s noisy ire.

Mr. Putin understands this too though perhaps not well enough. The Russian leader might witness the speed with which Mr. Trump is sending his high-budget trade war straight to video after it bombed with financial markets. There won’t be a deal if it doesn’t meet Mr. Trump’s political needs. If not, then it’s back to fighting against a renewed NATO commitment, however reflagged, to support Mr. Putin’s victim. Mr. Trump won’t like it either but he won’t have a better choice.

In the theatrics of bargaining, the path is often fairly obvious. The current tussle is one of those cases.

Mr. Trump seeks a grand minerals deal with Ukraine and a European label on Ukraine’s future arms deliveries so he can say the U.S. is no longer being taken to the cleaners by nefarious foreigners.

Ukraine isn’t likely to get back land it doesn’t control, but Russia’s occupation will be hampered by its continuing illegality. Not strange is that Mr. Trump seeks a carve-out for Crimea (a Biden administration likely would have done the same). Strange is that he’s not getting more for it. Trumpies say the Kremlin has relaxed its demands for a military neutering of Ukraine. Those demands should always have been nonstarters.

As for the criticism floated by many who find the Trump effort wanting: But Mr. Putin will always be able to restart the war! Yes. Not ontologically conceivable is a deal that would relieve the allies of having to prepare for a future war with Russia. The deal isn’t going to cure cancer either. The test is whether it closes off certain risks for the U.S. while leaving NATO and Ukraine better positioned for deterring Moscow for the long term, which is the eternal nature of state relations.