Back to Kinzler’s Global News Blog

The Economist, March 14

Trouble in Upper Nile : Another civil war looms in South Sudan

It could merge with the one in neighbouring Sudan, to catastrophic effect

Full text :

Residents of Juba, the capital of South Sudan, are familiar with violence. When civil war erupted in 2013, two years after independence from Sudan, the city was the scene of ethnic massacres and looting. After a ceasefire collapsed in 2016, Juba was a war zone for days. By the time the conflict ended in 2018, more than 400,000 people had been killed.

Many South Sudanese worry that Juba could soon be consumed by violence again. In 2020 the two main adversaries in the civil war formed a unity government. Yet the truce between Salva Kiir, the president, and Riek Machar, the vice-president, and their respective ethnic groups, Dinkas and Nuers, looks increasingly shaky. If it collapses, fighting could quickly engulf the country. Worse still, it could merge with Sudan’s civil war across the border.

The latest escalation came on March 7th when a general and multiple soldiers were killed in an attack on a UN helicopter by a Nuer militia known as the White Army, which fought alongside Mr Machar in the civil war. They had been trying to leave Nasir, a town engulfed in fighting in the oil-producing Upper Nile state near the border with Sudan (see map). Mr Kiir has had several of his rival’s allies arrested since the violence erupted last month.

The power-sharing deal has always been fragile. But the war in Sudan has made things much worse. For the past year it has prevented the export of about two-thirds of South Sudan’s oil—the petrostate’s economic lifeline. Mr Kiir, who relies on oil money to hold his government together, has embarked on a firing spree, ditching several close allies. He “feels threatened” by his lack of resources, says Daniel Akech of the International Crisis Group (ICG), a Brussels-based think-tank.

A succession struggle is adding to the uncertainty. The 73-year-old Mr Kiir is reportedly unwell and believed to be grooming a close adviser as his replacement. Veterans in the ruling party are said to be unhappy with his choice of successor.

The immediate trigger for the current crisis may be regional. Sudan’s army is understood to resent Mr Kiir’s perceived closeness to the Rapid Support Forces, the army’s adversary in Sudan’s civil war. Sudanese troops may be arming the White Army in response. By contrast Uganda, another neighbour, has sent troops to Juba to shore up Mr Kiir’s government. When outsiders get involved, local conflicts in South Sudan tend to turn into full-blown war, says Alan Boswell, also of ICG.

For now, the fighting remains far from the capital. Regional leaders, who convened a virtual emergency summit on March 12th, want to keep it that way. So do outsiders. “This region cannot take another war,” says Nicholas Haysom, head of the UN mission in South Sudan. Sadly, that does not mean it won’t get one. ■

https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2025/03/13/another-civil-war-looms-in-south-sudan

The Economist, March 8

International finance : Aid cannot make poor countries rich

For decades, officials have promised to raise economic growth. For decades, they have failed

Full text : https://kinzler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/8-mars-4.pdf

Link: https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2025/03/06/aid-cannot-make-poor-countries-rich

The Economist, February 22

No end in sight : Rwanda tightens its grip over eastern Congo

The Congolese government has lost control of the region

Full text:

Rulers of the Democratic Republic of Congo have rarely, if ever, fully controlled the east of Africa’s second-largest country. Kinshasa, its capital, is 1,500km from the provinces (South Kivu, North Kivu and Ituri) that border the other Great Lakes countries (Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda). The advance of M23, a Rwandan-backed rebel group, starkly reveals the Congolese state’s weakness. The region may be in for a third instalment of the wars that have blighted it since the 1990s.

On February 16th soldiers from M23 marched single-file through the streets of Bukavu, eastern Congo’s second-largest city. The beleaguered remains of the Congolese army had retreated without a fight. Rebel fighters toting grenade-launchers and machine-guns took triumphant selfies in the city’s main square.

The capture of Bukavu, South Kivu’s capital, came three weeks after M23 took Goma, its counterpart in North Kivu and the east’s largest city, with the help of Rwandan troops. The unilateral ceasefire the group declared amid African and Western condemnation of its seizure of Goma lasted about as long as it takes to reload a machine-gun. Soon M23 was on the march through South Kivu, supported by Rwanda’s Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 drones, according to Western officials.

Rwanda, which has a territory 1/90th of Congo’s, now in effect controls all of Lake Kivu. Congo’s army has pulled out of the strategic airport of Kavumu, near Bukavu, alongside thousands of troops from its main ally in the region, Burundi. The loss of this airport is an enormous blow, as it cuts off the Congolese army’s supply route. “Soldiers are leaving on foot, the officers are leaving by boat,” said a Bukavu-based researcher, who declined to give his name for safety reasons. “There’s no more military logistics, no more resupply.”

In Kinshasa the mood is grim. International sanctions on Rwanda, long a Congolese demand, have not materialised. Recent summits of African leaders on eastern Congo have had no impact on the ground. Felix Tshisekedi, Congo’s president, has not addressed the nation since January 29th, when he vowed that a “vigorous and co-ordinated response” was under way. Western embassies in Kinshasa, including those of America and Britain, have evacuated most of their staff, fearing that the situation in the capital may deteriorate.

As if Mr Tshisekedi needed further reminding of his army’s weakness, on February 18th Ugandan troops were said to be in Bunia, the capital of Ituri. It is unclear if the Ugandans are there as friends or foes. In 2021 Mr Tshisekedi authorised Ugandan soldiers to enter Congo to help root out jihadists. But in the days before Ugandan troops entered Bunia the head of Uganda’s army, General Muhoozi Kainerugaba, posted on social media that he planned to attack the city. Mr Kainerugaba, who is the son of Yoweri Museveni, Uganda’s president, is notorious for buffoonery. He once threatened to conquer Rome if Giorgia Meloni, now Italy’s prime minister, refused his bride price of 100 prize cows.

But Western officials are taking seriously the notion that Uganda may exploit Congo’s weakness. With M23 and Rwanda consolidating control over eastern Congo, the thinking goes, Uganda may move in to protect its own interests. This suggests the region could be in for a replay of the second Congo war of 1998-2003. Back then, Rwanda and Uganda sent their armies into Congo to vie for influence, with devastating effects on Congolese civilians.

One Bunia resident says the armed groups around the city are “on maximum alert, waiting for when the provocations start”. He adds: “We hope for calm, that’s our wish.” He is unlikely to get it. ■

The Economist, February 21

Generation Hustle : How to help young Africans thrive

As the rest of the world ages, young Africans are becoming more important

Full text:

Some generations come of age just as their countries rise economically. Think of America’s baby boomers, China’s millennials and perhaps India’s Generation Z. But there is another globally significant cohort that receives far less attention—what this week we call Africa’s “generation hustle”.

The sheer size of this group means that they will shape the world. Over 60% of people living in sub-Saharan Africa are younger than 25. By 2030 half of all new entrants to the “global labour force” will come from sub-Saharan Africa. By 2050 Africa will have more young people than anywhere else.

As countries in Europe, Asia and the Americas age and shrink, Africa’s population will continue to grow and remain youthful. Understanding this generation and their adversities is an urgent matter not just for Africans, but for everyone.

They are likely to surprise you. Young Africans are better educated and, thanks to the internet and social media, more aware of the wider world than their parents were. Unlike previous generations, they have no memories of colonialism. They combine an individualistic, enterprising outlook with piety and a streak of social conservatism. Much of that is bound up in a turn to Pentecostalism and its prosperity gospel, which highlights prayer as a path to material success.

For prosperity is what this generation lacks. They are frustrated with their shortage of opportunities. After a promising burst of activity in the 2000s, much of Africa has since endured over a decade of weak or non-existent growth. Stagnating economies are not creating enough good jobs to fulfil young people’s aspirations.

Young Africans have responded by finding creative ways to make ends meet. Some combine formal work with side hustles. Others juggle multiple gigs in the informal economy. But most would still much rather have a proper job.

Their lack of prospects is a disaster for a continent that badly needs its young people to realise their economic potential. Apart from causing individual anguish, it is also a risk to democratic stability. Young people on the continent are sceptical of the political systems that have failed them. Recent protests in Kenya, Nigeria and Mozambique have shown that their dissatisfaction can threaten governments. Frustration at their lack of opportunities and at politicians’ indifference to their plight is tempting some members of generation hustle to put their hope in strongmen and authoritarian politics.

The threat will spill across borders. More than half of young Africans say that they want to leave their own countries and make their fortunes abroad. For African governments and the world at large, it is therefore important to harness the hustle.

Some of the necessary changes in attitude are already in place in rich countries, where young Africans are making their mark. Their continent’s cinema and music are taking the world by storm. Restaurateurs have won Michelin stars in London. Entrepreneurs have enriched the startup scene in Europe and America. Done right, emigration will help host countries arrest demographic decline and fix labour shortages. Host societies will also benefit from young Africans’ enterprise, just as the diaspora will channel money, skills and ideas back to Africa.

Home is where the start is

Yet the most important changes should happen at home. As we argued in our special report earlier this year, African governments need to reform their economies. If they want to create more opportunities for ambitious youngsters they need to focus on growth. Young Africans already know that they need prosperity to achieve their dreams. They have the can-do mindset to do their part. It is up to their governments to enable them to thrive. ■

https://www.economist.com/leaders/2025/02/20/how-to-help-young-africans-thrive

The Wall Street Journal, February 17

Russia’s Side Quest to Dominate Africa: Hijack a Videogame

How a propaganda project reinvented ‘Hearts of Iron IV’ as ‘African Dawn’

Full text:

“Hearts of Iron IV” is a fan favorite in the panoply of online strategy games. Its legions of players guide their chosen nations through the tumult of World War II in the hope of ending up on top. Some enthusiasts like it so much they modify, or “mod,” the source code to add new scenarios, such as what would happen if the Central Powers had won World War I, or perhaps introduce some elements from the “Star Wars” movies.

Other mods are a little different. One revived the crusades of the 11th and 12th centuries and allowed players to enslave Muslims. Another placed Taylor Swift at the head of the Third Reich. The original game’s developer, Sweden-based Paradox Development Studio, tried to remove those from sites where they can be downloaded, only to see them pop up again.

Then the company found itself up against a new mod, this time coming from Russia.

The standoff began in late 2023, when Grigory Korolev, a young Russian influencer and gamer, received a call from a former employee with Wagner, the mercenary group founded by Yevgeny Prigozhin: Could he help develop a new mod that would take players to the messy patchwork of conflicts playing out in Africa’s Sahel region?

The call was from Anna Zamaraeva, who was now the deputy editor in chief of African Initiative, which the U.S. State Department describes as a propaganda outfit with ties to Russian intelligence agencies. The mod she had in mind was eventually dubbed “African Dawn.” Released last summer, it gives players the opportunity to lead a new Russian-backed alliance of military states in the arid strip between the Sahara and the tropical regions farther south, in what it pitches as “The Great African War.”

Korolev, who is 18, told The Wall Street Journal the mod is intended to show people around the world how Russia supports African countries to resist what he sees as the undue influence of the U.S. and Europe.

“The purpose of the game is to educate,” Korolev said. “We tell young people in different countries what is really happening on the Black continent. Before playing, many players didn’t know the names of many African countries, let alone the Sahel region.”

“African Dawn” begins on the day of a real-life military coup in Burkina Faso in September 2022. It asks players to choose a side aligned with either Russia or the West, mimicking how countries in the region such as Mali and Niger have since split into the Russian-backed Alliance of Sahel States from the older, Western-backed Economic Community of West African States.

Players then have to make a series of strategic decisions from drop-down menus to emphasize different features of their political bloc, strengthening ideology or prioritizing weapons production over agriculture as they try to outmaneuver and ultimately defeat their adversaries. With some careful strategizing, and a little luck, they could emerge as the dominant power in Africa.

Paradox has tried to remove “African Dawn” from various gaming platforms, saying it portrayed elements of genocide. The company says it tries to remove mods that promote racism or that seek to worsen real-world conflicts, but they keep returning to various platforms. Korolev estimates it has been downloaded around 50,000 times.

“Sadly, we have limited control over the mod’s development, content or distribution,” a Paradox spokesperson said, adding that the company was surprised and disappointed that its game was being used in this way.

Zamaraeva and Artem Kureev, the editor in chief of African Initiative, dispute the suggestion that “African Dawn” articulates genocidal themes, pointing out that the original game revolved around Nazi Germany’s attempt to dominate the world. Instead, they say it is designed to present some of the big issues playing out in Africa, and that far from being a propaganda shop, African Initiative aims to promote a deeper understanding between Russians and their counterparts across Africa.

“Our core values are objectivity, building a multipolar world, and achieving the equality of all nations,” they said.

Even before the internet, games played a role in military operations. During World War II, the British and U.S. military hid money, maps and tools in Monopoly board games and sent them via fake charities to soldiers and airmen held in German prison camps. Many prisoners of war successfully escaped with their help, according to Phil Orbanes, a game inventor and author who spent decades working for Parker Brothers, the maker of Monopoly.

Former U.S. Special Forces operatives have worked with American videogame company Activision Blizzard as advisers on its phenomenally successful Call of Duty first-person shooter franchise, while the U.S. military has used such games to boost recruitment.

Russian gamers have previously taken advantage of popular online games, including Microsoft’s Minecraft, to spread propaganda about Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, including by re-enacting real-life battles such as the fight for the Ukrainian town of Soledar, which began in August 2022. A new Russian-made board game follows some of the gameplay of Monopoly by allowing players to swoop in after the Russian invasion and buy and own Ukrainian cities such as Odesa, Kyiv and Mariupol.

But “African Dawn” is one of the first known instances of a state-linked actor releasing a propaganda-type mod of a popular online videogame, said Galen Lamphere-Englund, co-founder of the Extremism and Gaming Research Network, a U.S.-based nonprofit.

“How effective this is remains to be seen, but I think it’s a smart campaign,” he said.

Mods of popular online games can be simple or extremely complex, with a total game overhaul taking a team of developers many months or even years. Modders can change data files within the game to change its look.

Often these mods are completely legal and, if done well, are essentially free labor for game companies. Players like mods because they gives them the chance to play through the games again, with different countries, characters and outcomes.

‘African Dawn’ players use drop-down menus to emphasize different features of their political bloc. Photo: Grigory Korolev

But they can also spread violent or extremist ideas, leaving videogame companies playing a game of “Whac-A-Mole.” The amount of resources and attention developers devote to such efforts varies, and problematic content isn’t always detected quickly, if at all.

This provides an opportunity for individuals or entities with a specific political agenda.

Jesper Falkheimer, a professor of strategic communication at Lund University in Helsingborg, Sweden, has researched how gaming platforms can be potential tools for disinformation and manipulation, which he sees as a growing trend. “Videogames offer an immersive and easily accessible arena for persuasion and propaganda for hostile states, organized criminals and extremist groups,” he said. “We think that the immersive use of videogames increases the effect, compared to traditional media platforms.”

Moscow has long sought to present itself as a benefactor to countries across Africa and much of the developing world, motivated in part by the hope of gaining permanent access to the Indian Ocean. During the Cold War it took sides in civil wars and supported leftist regimes in countries such as Ethiopia and Mozambique.

More recently, the Wagner paramilitary group built a portfolio of businesses from gold mining to brewing beer across a swath of the continent, often sponsoring soccer games and planting positive stories in the local media to influence perceptions of Russia’s growing involvement in the region. The Kremlin took control of Prigozhin’s group after he turned against Russian leader Vladimir Putin and was killed in a plane crash.

African Initiative first appeared a month later and Korolev’s involvement was crucial for generating some buzz for “African Dawn.”

Known as Grisha Putin (“Grisha” is a diminutive of “Grigory”), he has built a large following on YouTube by streaming first-person Call of Duty-style shooter games and military-strategy games, often wearing a military uniform and declaring that “Nazi pigs don’t deserve to be remembered,” using a common derogatory term directed at Ukrainian soldiers. He has used his fame to drum up donations for the Russian war effort, often for drones, while Russian soldiers have been known to send him mementos from the front lines, including Ukrainian combat jackets.

In Korolev’s worldview, you are usually either with Russia or against it. “African Dawn” is actually a little more complex.

Much of the gameplay draws on recent African history. It largely revolves around the rise of Thomas Sankara, a military officer in Burkina Faso who seized power in the 1980s and tried to introduce a radical pan-Africanism across the continent before he was assassinated a few years later.

Players can choose to play as any of the countries in the region, including factions as the Islamist militant group Boko Haram, which is fighting an insurgency in northern Nigeria, or as the U.S., France or Russia. Those selecting Russia are tasked with breaking the Sahel nations’ old ties to France and the West, much as Moscow is attempting to do in real life.

But people who have played the game say Burkina Faso might be the most difficult and rewarding country to play. The country’s current leaders have styled themselves as the heirs to Sankara, and the game pushes their ambitions a step further, with some help from Russia of course.

Some players find it provides a compelling message.

“I really like how the game portrays Russian soldiers as saviors from the new colonial power of Western capitalism,” said Timofei Roslyakov from Chelyabinsk, Russia, who played “African Dawn” recently.

He said he ended the game on a good note, “having completely liberated West Africa from French and American influence, and peace and tranquility prevailed throughout.”

The Economist, February 7, pay wall

The long au revoir : France’s bitter retreat from west Africa

The danger is a security void now opens up

Extraits:

For nearly a decade the French embassy in Bamako, the capital of Mali, was the political nerve centre of a counter-terrorism operation that spanned five countries. The sprawling fortress still resembles a military base. But its guard towers and walls topped with razor wire are as much a relic of a bygone era as the French-built colonial avenues that surround it.

Following the ignominious end in 2022 of Barkhane, the multi-country anti-terrorism operation it launched at Mali’s request in 2013, France has given up most of its military footprint across west Africa with astonishing speed. By the end of the year, the only remaining French base in Africa will be in Djibouti. Driven by pressure from the military dictatorships that have taken power across the Sahel and by anti-French sentiment in nearby countries, the abrupt exit marks a sea change in France’s relationship with its former colonies. It also raises the question of what will fill the void left by the French presence.

Unlike other former colonial powers, France kept permanent military bases in Africa long after the continent’s countries won their independence. At times it acted as a regional gendarme, propping up leaders and beating back jihadists. No more. Military juntas have forced French troops out of Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso (see map). Chad took over the French base there in January. In December Ivory Coast and France agreed on the withdrawal of French forces. Senegal has declared that French soldiers will leave in 2025.

France wanted a more orderly exit. In a speech in Paris on January 6th, President Emmanuel Macron lamented “ingratitude” in the Sahel for France’s efforts to fight jihadists there. Mr Macron’s comments, widely criticised in the region, marked an awkward twist to his promise, upon taking office in 2017, of a more equal partnership with France’s former colonies.

Yet the more important question is what the French withdrawal will mean for security across the region, which is being menaced by jihadism, separatism and military rule. For a period, it seemed as if Mr Macron’s revamped version of Barkhane was making tactical gains against jihadist groups, and helping to improve the appalling insecurity for civilians in some parts of the Sahel. After Mali’s new junta, which seized power in 2020, hired mercenaries from Russia’s Wagner Group, relations took a turn for the worse. In 2022 the French quit Mali and shut down Barkhane, and the regional domino effect began.

Military leaders in the Sahel, who have increasingly turned to Russian-backed mercenaries to help fight separatists and jihadists, have cheered the French departure as the end of a neo-colonial hangover. (…)

In practice that has meant that AES countries have jettisoned efforts to negotiate with rebels of all stripes in favour of full-bore militarism. Yet this approach has fared little better than the French operation. In Mali the army, backed by Russia’s Wagner Group and Turkish Bayraktar drones, made important territorial gains in the north. In 2023 it seized Kidal, the symbolically significant stronghold of Tuareg separatists that French troops blocked Malian forces from entering a decade before. (…)

But it has failed to stop the entrenchment of Islamic State in the north, or to stem worsening violence elsewhere in the country. Urban areas considered secure have recently seen attacks. In September Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), a jihadist group linked to al-Qaeda, attacked a police academy and an airport in Bamako, the first major terrorist incident in the Malian capital for nearly a decade. “They say things are better since they captured Kidal,” complains a local businesswoman. “But why hasn’t that stopped terrorists from bombing the city?”

Elsewhere in the region, things are hardly better. (…)

Unlike the French troops and UN peacekeepers, local armies and the mercenaries that support them care little for protecting civilians. In the first six months of 2024, 3,064 civilians were deliberately targeted and killed in the Sahel, up from 2,520 in the last half of the previous year, according to ACLED, a conflict monitor. In 2022 the Malian army and Wagner forces killed over 500 civilians, mostly women and children, in a single operation, according to UN investigators. “Before, people were afraid of the terrorists,” says Fatouma Harber, a Malian journalist. “Now they are afraid of the Malian army and Wagner.”

Yet there appears to be broad support across the Sahel for the departure of French troops. However much worse things may have got since they left in 2022, many Malians point out that security had been deteriorating since their arrival a decade earlier. (…)

The new arrangement marks the “demilitarisation” and “normalisation” of France’s tie to Africa, says a presidential adviser. The hope is that 2025 will mark the end of an anachronistic high-visibility footprint that exposed France to accusations of neo-colonialism, without precluding modernised defence aid. Full training exercises or operations involving the dispatch of planes or soldiers from France may be carried out, only if requested by African partners, under the Paris command.

Where does that leave the Sahel? Regional observers say there are signs the juntas are realising that they cannot defeat insurgents by brute force alone. Niger’s junta recently sent envoys to jihadist leaders. Regional negotiations devoid of external influence could produce deals that reduce the violence. More likely, for now, the toxic new alliance of military rulers and Russian mercenaries will continue to cause misery for beleaguered civilians.■

https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2025/02/01/frances-bitter-retreat-from-west-africa

Le Point, 6 février, article payant

Un conflit oublié et la tragédie d’un peuple

LA CHRONIQUE DE GÉRARD ARAUD. En 1994, la minorité tutsie du Rwanda fut victime d’un génocide commis sur ordre du gouvernement qui s’appuyait sur la majorité hutue. À l’époque, la France s’était fourvoyée.

Extraits:

Je vais vous parler d’un conflit qui a coûté la vie à des millions de civils dans l’indifférence du monde et qui vient de connaître un nouveau rebondissement qui annonce de nouvelles souffrances pour une population épuisée d’épreuves.

En 1994, la minorité tutsie du Rwanda fut victime d’un génocide commis sur ordre du gouvernement qui s’appuyait sur la majorité hutue. Il fit entre un demi-million et huit cent mille victimes. Hélas, la France de François Mitterrand s’était fourvoyée dans ce conflit qui ne concernait pourtant pas ses intérêts.

Certes, elle venait de retirer le contingent qui soutenait l’armée rwandaise dans son combat contre le FPR – Front Patriotique du Rwanda –, d’obédience tutsie, qui avait envahi le pays à partir de l’Ouganda lorsque l’innommable eut lieu, mais il n’en reste pas moins qu’elle entretenait des relations étroites avec un gouvernement responsable d’un génocide. Un rapport rédigé par l’historien Vincent Duclert à la demande d’Emmanuel Macron décrit d’ailleurs en détail les erreurs commises par notre pays – en réalité par l’Élysée – dans cette triste affaire.

Le M23 dans le Kivu

Après sa victoire et sa prise de pouvoir à Kigali, on conçoit que le FPR et son chef, Paul Kagamé, virent dans notre pays un adversaire, en tout cas une puissance inamicale. Par ailleurs, une partie des milices génocidaires s’étaient réfugiées dans la province congolaise du Kivu, le Rwanda pouvait à juste titre voir dans les FDLR (Front démocratique de libération du Rwanda) une menace sans même évoquer un désir légitime de punir les assassins de tout un peuple. Or, la République démocratique du Congo (RDC) était incapable non seulement de désarmer les FDLR, mais aussi de faire régner un minimum d’ordre au Kivu où ce mouvement commençait là aussi à persécuter la minorité tutsie.

Le Rwanda a donc pris la situation en main en intervenant dans cette province que ce soit directement ou plus souvent par le biais d’un mouvement rebelle qu’il contrôle, le M23. Les services de renseignements occidentaux ont toutes les preuves de cette sujétion, ne serait-ce que par l’interception des instructions transmises du Rwanda.

À l’origine défensive, cette présence dans le Kivu a changé de nature au fil du temps. Il y a longtemps que les génocidaires de 1994 sont morts ou neutralisés. En revanche, la RDC reste largement un État failli tandis que la force des Nations unies déployée depuis des décennies dans la région, la Monusco, manifeste toujours la plus évidente inefficacité.

Le Rwanda, la Prusse de l’Afrique de l’Est

Or, le Rwanda de son côté est devenu, à force de travail et d’autoritarisme, la Prusse de l’Afrique de l’Est, un petit État militarisé, prospère et expansionniste. Peuplé de 13 millions d’habitants pour une surface de 26 000 km2, il étouffe dans des frontières trop étroites alors qu’à ses portes, la RDC contrôle et exploite bien mal un territoire de 2,3 millions de km2 aux immenses ressources minérales. La tentation était trop forte et le Rwanda y a succombé ; le M23 lui sert désormais d’instrument pour occuper et piller le Kivu.

Il est d’ailleurs soudain devenu un grand exportateur de minerais, dont le coltan, indispensable pour les téléphones portables, et tout indique, notamment les rapports des Nations unies, qu’une bonne partie de cette production provient du Kivu par le biais de l’exploitation directe de mines ou par l’achat des matières auprès de mineurs artisanaux. Ses exportations de minerais sont d’ailleurs passées sans explication de 770 millions de dollars en 2022 à 1,1 milliard en 2023, ce qui correspond à la prise de la mine de Rubaya par le M23.

Le monde se tait. Il est vrai que, d’un côté, le Rwanda émeut en tant que victime d’un génocide, et que, de l’autre, il impressionne par l’efficacité de ses structures étatiques. À ce dernier égard, la RDC est tellement un contre-exemple qu’elle ne suscite guère la solidarité. Enfin, les entreprises chinoises ne ressentent aucune gêne à s’approvisionner ainsi en minerais rares. Cela étant, les ambitions d’un Kagame qui fait par ailleurs assassiner ses opposants en exil chez ses voisins africains ont fini par inquiéter les puissances de la région. Afrique du Sud, Angola et Tanzanie sont intervenus à un moment ou à un autre pour soutenir une RDC désespérément inefficace : la première déploie encore aujourd’hui un contingent au Kivu.

C’est dans ce contexte troublé, qui pèse sur une population civile martyre, que le Rwanda a récemment pris l’offensive pour s’emparer de l’ensemble de la province congolaise. Le M23 a balayé non seulement les Congolais, mais a bousculé également les Sud-Africains. Kagame triomphe. L’Occident qui n’a cessé de soutenir financièrement le Rwanda commence timidement à protester mais ne fera rien.

Pourquoi se fâcher avec le vainqueur ? Assistons-nous à un nouvel exemple de l’effondrement de tout ordre international, qui laisse libre les prédateurs de réaliser enfin leurs ambitions sans crainte d’une intervention extérieure ? Verrons-nous en Afrique un retour au jeu traditionnel des puissances avec une coalition qui se dresserait contre le Rwanda ? Ce conflit est tout sauf anecdotique non seulement par les souffrances qu’il inflige aux populations civiles, mais par le symptôme qu’il représente du monde qui vient.

https://www.lepoint.fr/debats/un-conflit-oublie-la-tragedie-d-un-peuple-02-02-2025-2581321_2.php

The Economist, January 31, pay wall

High stakes in the Great Lakes : The fall of Goma heralds more bloodshed in eastern Congo

Rwanda’s reckless invasion raises the risk of a wider war

Extraits:

“There are no more places for the dead,” says Marie Kavira-Nvungi, a nurse at a hospital in Goma, the largest city in the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo. The morgue is full. Wounded patients lie on the floor waiting for treatment. Among them are children injured by shrapnel and explosives. The pharmaceutical depot has been looted, depriving patients of medicines. “The situation is becoming difficult,” adds Ms Kavira-Nvungi, with stoical understatement.

The scene is the result of the invasion of Goma on January 27th by M23, an armed group under the control of Rwanda, Congo’s neighbour, which abuts the city. Paul Kagame, Rwanda’s president, has escalated a crisis whose origins go back decades. More instability in Congo, which saw two catastrophic wars between 1996 and 2003, is almost certain. As African and Western states are distracted or indifferent, there is little to stop a wider conflict.

Goma is more than 1,500km east of Kinshasa, Congo’s capital, but just 100km west of Kigali, the Rwandan one. It is the hub of what Mr Kagame sees as Rwanda’s sphere of influence. He claims the Congolese state has failed to get a grip on its war-torn east and co-operates with his country’s enemies. Mr Kagame singles out a militia known as the FDLR, which has its roots in the ethnic Hutu groups that tried to exterminate Mr Kagame’s Tutsis in the genocide of 1994. Those close to him add that the infrastructure Rwanda has built near the border—including luxury tourist lodges for seeing gorillas—is at risk from any group or Congolese army division with an armed drone.

Yet what remains of the FDLR is a motley assemblage that presents little threat to Rwanda’s army. Rwanda is the main sponsor of instability in the region that Mr Kagame claims Congo is failing to pacify. Its elites harbour dreams of a “Greater Rwanda”, arguing that its colonial borders do not reflect its history. Congo’s vast mineral wealth is another motive to meddle. M23 controls coltan supply chains. Congolese gold is regularly smuggled out of Rwanda.

When Félix Tshisekedi became president of Congo in 2019, Mr Kagame welcomed his victory in dubious elections. But relations soon soured. (…)

The rhetoric on both sides has long been rising. Mr Kagame has implied support for the idea of a greater Rwanda. Mr Tshisekedi has likened Mr Kagame’s territorial ambitions to those of Adolf Hitler, and suggested he wants to change the regime in Kigali. (…)

In Goma M23 has seized full control, after some brief resistance from Congolese special forces and pro-government militias known as Wazalendo. Some Congolese soldiers and militiamen ditched their uniforms before hiding or fleeing. Your correspondent found uniforms that had been thrown over the wall of his hotel. Foreign troops meant to help the Congolese army have melted away. Romanian mercenaries procured by Congo have left by bus for Rwanda. A deployment of southern African forces has been humbled; South Africa says 13 of its troops have died in recent skirmishes. Members of one of the world’s largest UN peacekeeping missions, known as MONUSCO, are either sheltering in their bases or have left the country.

The city has been devastated. (…)

Yet Rwanda calculates that the West will not enforce sanctions that would compel it to reverse course. Nor does any African country have the focus or clout to stop the bloodshed. (…)

What happens next? M23 seems set to administer Goma, presumably with Rwandan assistance. But Mr Kagame may go further. A Rwandan official suggests that M23 will advance on South Kivu, raising the risk of further conflict between Rwanda and neighbouring Burundi, whose troops have also been fighting against M23. There is a possibility that Mr Kagame wants a reprise of the 1990s, when his army marched all the way to Kinshasa to topple Mobutu Sese Seko, the dictator of what was then Zaire.

That is unlikely. But Mr Tshisekedi seems keen to use an upsurge in jingoism for his own ends; some fear he wants to try to remove a constitutional limit on his staying in office beyond the end of his second term in 2029. His opponents, by contrast, will see his humiliation as an opportunity to get rid of him. They include political groups that are closely allied with M23.

Either way, the fall of Goma is a seismic moment in the modern history of the Great Lakes. Rwanda’s actions will continue to be met with disapproval. But Mr Kagame thinks he can get away with it. The past 30 years suggest that he is right.

The Economist, January 29, pay wall

Africa in peril: : Rwanda does a Putin in Congo

To understand the seizure of Goma, consider a parallel with Ukraine

Extraits:

SOMETHING AWFUL is happening in Congo. A rebel group called M23 seized control of Goma, the biggest city in the east of the country, on January 27th, killing several UN peacekeepers and prompting hundreds of thousands of locals to flee. Hardly anyone outside central Africa knows who M23 are or what they are fighting for. So here’s a helpful analogy: Donbas.

In 2014 Vladimir Putin grabbed Donbas, an eastern region of Ukraine, and pretended he had not. As a figleaf he used local separatist forces, which Russia armed, supplied and directed. These forces, he claimed, were protecting ethnic Russians from persecution by bigoted Ukrainians. The Kremlin denied that the Russian army itself was on the ground assisting the rebels, though it was. Later, after Mr Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, he dropped the pretence that the breakaway statelets in Donbas were “independent” and forcibly annexed them in 2022.

Rwanda’s dictator, Paul Kagame, has copied these tactics in eastern Congo. The M23 rebels are armed, supplied and directed by his regime. They claim to be protecting Congolese Tutsis from persecution, but this threat is exaggerated. M23 is in fact a proxy for Rwanda, allowing it to grab a big chunk of Congolese territory while pretending not to. The UN estimates that thousands of Rwandan troops have crossed into Congo to assist with this land grab. Rwanda denies what observers on the ground can plainly see.

The consequences are horrific. After years of fighting some 8m people have been driven from their homes in Congo, including 400,000 in the past month. In much of the east, men with guns rape and plunder with impunity. Precious minerals are systematically looted; Rwanda, which mines little gold at home, has mysteriously become a large gold exporter. And now Goma, which was previously home to 2m people, is under occupation, with only a few pockets of resistance remaining. Congo’s government says Rwanda’s actions amount to a declaration of war. Actually it is an undeclared war, an act of stealthy colonialism. (…)

The parallel between Russia and Rwanda is imperfect. Rwanda has not formally annexed any of its neighbour’s land. Another difference is that whereas Ukraine was a functioning democracy when Mr Putin invaded it, Congo is chaotic and atrociously governed. Dozens of loosely organised armed groups ravage the east. Rwanda is far from the only predator, but it is the most powerful. Its army is disciplined, motivated and competent, which is why it can bite chunks out of a country 90 times Rwanda’s size.

Following the Donbas model, Rwanda has informally created something that looks a lot like a puppet state on Congolese soil. And it may not stop at Goma. (…)

The global taboo against taking other people’s territory is crumbling. Mr Putin is the prime offender, spilling rivers of blood for soil. China menaces Taiwan and claims other countries’ territorial waters. And now President Donald Trump talks of expanding American territory. Against such a background, it is hardly surprising that other leaders have concluded that imperialism is back in fashion. (…)

Other Western governments are torn. Many have a soft spot for Mr Kagame’s Rwanda. Its domestic orderliness makes it easier to run development projects there. Its soldiers serve in UN peacekeeping operations and protect French gas operations in Mozambique as part of an EU-funded mission. Mr Kagame, a former rebel leader, retains kudos for stopping Rwanda’s genocide three decades ago. Donors often give Mr Kagame the benefit of the doubt and keep bankrolling his government.

They should be much tougher. Rwanda is heavily aid-dependent, with grants covering 12% of its budget and most of its external debt on concessional terms. They should lean harder on Mr Kagame, as they have in the past. America, which has strong military ties with Rwanda, could change Mr Kagame’s incentives with a phone call. Other African states should speak up, too.

The alternative—to let Mr Kagame keep his Donbas—is much worse. A world in which the strong seize territory from the weak would be a scarier, more violent place. In Africa, especially, there are countless objections to today’s frontiers, but attempts to move them have usually ended in catastrophe. If blatant breaches of borders are allowed to stand, there will be more of them. ■

https://www.economist.com/leaders/2025/01/28/rwanda-does-a-putin-in-congo

The Economist, January 28, pay wall

Chaos in Eastern Congo : Rwanda’s reckless plan to redraw the map of Africa

The fall of Goma could trigger another Congo conflict

Extraits:

THE RESIDENTS of Goma are no strangers to war. The largest city in the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has long been a refuge for those fleeing from violence elsewhere in one of the world’s most blood-soaked regions, where more than 100 armed groups compete for land, loot and political influence. On January 26th the most sophisticated of these militias, a group known as M23, brought war to the city itself. Its apparent seizure of Goma, the culmination of more than two years of resurgent violence by the previously dormant group, illustrates the enduring weakness of the Congolese state. It is also a worrying sign that M23’s patron, Rwanda, may be willing to use its strength to redraw the map of the region—and, in doing so, risk another catastrophic African war.

The origins of events in Goma go back decades. Between 1996 and 2003 Rwanda and other regional powers fought over the spoils left by the dictatorship of Mobutu Sese Seko, who misruled Congo, which he renamed Zaire, from 1965 until 1997. Rwanda claims its interest in eastern Congo has been to root out remnants of those who fled there after committing the genocide of 1994, and to protect Tutsis, the ethnic group partly extinguished by that highly organised orgy of killing. But Rwanda has long been suspected of using proxies for other reasons, too, such as plundering Congo’s mineral wealth and pulling the area into its sphere of influence.

The most important proxy has been M23, which takes its name from a moribund peace deal signed on March 23rd 2009, between a previous Tutsi-led group and the Congolese government. (…)

Rwanda denies giving any support to M23. But in 2022 a UN report found “solid evidence” that Rwandan troops were fighting alongside it. M23 has used surface-to-air missiles and armoured vehicles that mean it resembles a division of the Rwandan army more than it does a ragtag militia. In the weeks leading up to the latest offensive Rwanda jammed GPS devices used by anti-M23 forces, according to Western diplomats. (…)

The fall of Goma underlines the failure of Mr Tshisekedi’s pledge, upon taking office in 2019, to bring peace and order to eastern Congo. The latest attempt at peace talks intended to stem M23’s advance, brokered by Angola, fell apart in December. The Congolese army is corrupt and incompetent. After most of its defensive lines collapsed on January 26th grim-faced soldiers have been driving around in jeeps in the centre of town, looking for ways out of the city. Multilateral efforts have fared little better. The 14,000 UN peacekeepers, known by the acronym MONUSCO, have been undermined by their own track record (they have struggled to keep the peace and several blue helmets have been accused of sexual abuse), as well as Congo’s vacillation about whether or not their mandate would be extended (which it ultimately was for a further year in December 2024). The civilians among MONUSCO were at the time of writing trying to cross the border to safety—in Rwanda. A deployment of troops from southern Africa, led by South Africa, has proved largely useless. Meanwhile hundreds of European mercenaries, known locally as “Romeos” because most are Romanian, have given up their weapons and positions in exchange for their safety.

What happens next? Back in 2012, pressure on Paul Kagame, Rwanda’s president, by donor countries including America preceded a swift ouster from Goma of M23 by UN peacekeepers. That scenario seems less likely this time around. A flurry of diplomatic efforts is under way in response to what Congo’s government has called a “declaration of war”. William Ruto, Kenya’s president, has called for talks between Congo and Rwanda. In a rare display of agreement at the UN Security Council its members called on M23 to withdraw from Goma and denounced “the unauthorised presence in the Eastern DRC of external forces”.

For many observers, however, that implicit criticism of Rwanda is too little, too late. For 30 years it has been seen by the West as a stable country in an unstable region. America has lavished aid on it. Britain wanted it to host asylum seekers. The EU has struck minerals and infrastructure deals with Mr Kagame and given his army 40m euros ($42m) to fight an insurgency in northern Mozambique. Yet even if Rwanda itself is a stable autocracy, by fomenting violence in its neighbourhood, it has proved again that it is an exporter of chaos. ■

The Economist, 15 janvier, article payant

Closing arguments : To catch up economically, Africa must think big

But it would require a new surge of ambition

Extraits :

(…) The demographic divergence could be a boon. African emigrants will be needed to do jobs in the rest of the world. They will send home remittances, which are already worth almost double the continent’s total fdi. African economies will inevitably grow as their populations swell, adding to global demand. If sub-Saharan Africa can repeat Asia’s transformation, it “will become the next major engine of global growth”, argues a research note by Bridgewater. Today, it says, the region is home to 15% of global population, accounts for just 3% of global output and provides 5% of growth. If sub-Saharan Africa were to raise its productivity growth from around 1% per year to 4% (close to India’s recent rate), by 2050 its share of world output would be 10%—and it would account for a fifth of global growth.

The risk, however, is that Africa combines high population growth with low or stagnant productivity growth—and that the Africa gap only widens. If current trends continue unchecked, this is what will happen. The Institute for Security Studies (iss), a South African think-tank, has published scenarios for the future of the continent. These “African Futures” incorporate data on a variety of factors including demography, productivity, financial flows, infrastructure and measures of human capital. Its “current path” makes for sober reading. By 2043, the year its forecasts end, median African gdp per person, adjusted for purchasing-power parity (ppp), will be about a quarter of the rest of the world’s, essentially what it is today. And Africa will still have 400m people in extreme poverty, the vast majority of the world’s destitute.

This special report has tried to explain the reasons for this disappointing path. These include the scarce use of technology in agriculture, the rise of unproductive, low-end services and the absence of a manufacturing revolution. Productivity is further hampered by small firms and small markets. Africa has perhaps just half of the investment it needs to close the gap. “Something drastic is needed to change this rather dismal forecast,” write the authors from the iss.

Yet there is a better way forward. The iss also forecasts a “combined scenario”, where it projects what would happen if African countries did most things right. These include making a quicker demographic transition, expanding education, increasing investment in infrastructure, boosting agricultural productivity and manufacturing, encouraging greater financial flows and implementing the African Continental Free Trade Area (afcfta). Under its most optimistic scenario the iss reckons the Africa gap would begin to close over the next 20 years. By 2043, gdp per person in ppp terms would be about a third of that in the rest of the world. Just 8% of Africans would live in poverty, rather than the 17% projected on the current path.

Viewed from 2025 that continent-wide tide seems unlikely to rise. More probably the gaps already visible between African countries will widen. Last year it had nine of the 20 fastest growing economies in the world, including Ethiopia, Rwanda and Ivory Coast. “Africa is becoming a split story,” argues Charlie Robertson, author of “The Time-Travelling Economist”. The countries that have seen fertility rates fall below three, as happened in Mauritius in 1979 and Morocco in 1999, have enjoyed demographic tailwinds, he argues, as families have been able to save more money, increasing the overall pool of investment and lowering interest rates. Kenya should pass this threshold in 2029, Mr Robertson points out.

“You need to discriminate between the different countries on the continent,” cautions Amit Jain, who spent many years in Africa and is now at the Centre for African Studies at ntu Singapore. He points to how Morocco is developing a commercial-agriculture sector and suggests that east African countries are doing better than their peers in west Africa in educating their children and expanding access to electricity. The likes of Kenya are well located to integrate into Asian firms’ supply chains, he adds. “Countries in the region might not hit $60,000 per capita but $15,000 is possible and would be a heck of an achievement.” (…)

Everyone with a stake in Africa must think big. Countries need development bargains that allow for the emergence of large firms and productive industries. Africa as a whole must make the afcfta a reality, giving it more bargaining power at international forums. Foreign countries need to face up to the reality that their current approach to development financing is nowhere near sufficient for Africa to transform its economies and respond to climate change.

Perhaps most important, Africa needs to recover a sense of ambition. In too many African countries the default approach is what Ken Opalo of Georgetown University calls “low-ambition/muddling-through developmentalism”, a “destination anywhere” approach which follows paths defined from outside without a clear sense of the paramount goal. There is an urgent need for African policymakers and business leaders to set their own far-reaching goals for economic transformation and rally their people behind them.

The stakes are high. Africa’s demographic boom has led to the idea that the 21st is the African century. It could yet be. But a quarter of the way into it, Africa had better hurry up. ■

https://www.economist.com/special-report/2025/01/06/to-catch-up-economically-africa-must-think-big

The Jerusalem Post, 14 janvier, article payant

Sudan: The real genocide

Whether you call it an obsession or antisemitism, social convenience or just ignorance, the international silence on the Arab genocide in Sudan adds up to the same thing: an egregious moral outrage.

The writer is founding director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies and author of more than 20 books about Jewish history and the Holocaust.

Full article here: https://kinzler.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/14-anvier.pdf

Link: https://www.jpost.com/opinion/article-837219

The Wall Street Journal, 12 janvier, article payant

Africa Has Entered a New Era of War

A surge in conflicts has gone largely unnoticed amid higher-profile wars in Ukraine and the Middle East

Extraits :

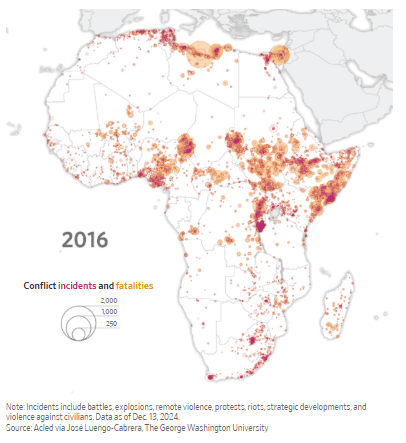

An unprecedented explosion of conflicts has carved a trail of death and destruction across the breadth of Africa—from Mali near the continent’s western edge all the way to Somalia on its eastern Horn.

Older wars, such as the Islamist uprisings in northern Nigeria and Somalia and the militia warfare in eastern Congo, have intensified dramatically. New power contests between militarized elites in Ethiopia and Sudan are convulsing two of Africa’s largest and most populous nations. The countries of the western Sahel are now the heart of global jihadism, where regional offshoots of al Qaeda and Islamic State are battling both each other and a group of wobbly military governments.

This corridor of conflict stretches across approximately 4,000 miles and encompasses about 10% of the total land mass of sub-Saharan Africa, an area that has doubled in just three years and today is about 10 times the size of the U.K., according to an analysis by political risk consulting firm Verisk Maplecroft. In its wake lies incalculable human suffering—mass displacement, atrocities against civilians and extreme hunger—on a continent that is already by far the poorest on the planet.

Yet, these extraordinary geopolitical shifts in sub-Saharan Africa have been overshadowed by higher-profile conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East. That has led to less attention from global policymakers—especially in the West—grossly underfunded humanitarian-aid programs and fundamental questions over the futures of hundreds of millions of people.

Africa is now experiencing more conflicts than at any point since at least 1946, according to data collected by Uppsala University in Sweden and analyzed by Norway’s Peace Research Institute Oslo. (…)

There is no single driver for the emergence and escalation of so many different conflicts across a huge and diverse geography. But, experts say, many of the most-affected states were left vulnerable after failing to settle on a strong mode of governance after independence—whether as functioning democracies or established authoritarian systems—or were destabilized during moments of once-in-a-generation political transitions. (…)

One inflection point was the year 2011, when, amid the pro-democracy uprisings of the Arab Spring, militaries from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization intervened in Libya to support rebel forces fighting the country’s dictator Moammar Gadhafi. With Gadhafi’s death and Libya’s descent into chaos, thousands of armed men moved south into Mali, reigniting a Tuareg rebellion against the government in Bamako that coincided with the global expansion of extremist ideologies promoted by al Qaeda and Islamic State.

“With the Sahel, it’s clearly a problem of Libya’s collapse and the highway of arms and ideology that that creates,” says Ken Opalo, a Kenyan academic and associate professor at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service. “So you get weak states, lots of guns and young men leaving Libya and ideologies coming all the way from Pakistan. Then everything is on fire.” (…)

From Mali, the jihadist insurgency spread across porous borders into Burkina Faso and Niger, where new military juntas frustrated with the failure to defeat the militants have kicked out French and other Western troops. It now threatens coastal West African states such as Benin and Ghana. (…)

Counting the dead in African conflicts is notoriously difficult. (…)

For Ethiopia, for instance, experts at the University of Ghent in Belgium have estimated that the two-year war between the government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front caused the deaths of between 162,000 and 378,000 civilians. Acled, whose analysts scour local news sources and contacts for real-time conflict data, counted fewer than 20,000 war fatalities from the fighting itself.

What is clear from the data is that civilians are much more likely to be deliberately targeted in conflicts in Africa than in many wars elsewhere. (…)

The intensifying conflicts have displaced a record number of Africans—most of them inside their own countries. The continent is now home to nearly half of the world’s internally displaced people, some 32.5 million at the end of 2023. That figure has tripled in just 15 years. (…)

Africa’s current conflicts haven’t prompted the outpouring of sympathy in the West that accompanied Russia’s invasion of Ukraine or the outrage ignited by Israel’s war in Gaza. There has been no equivalent to the Live Aid concerts motivated by the Ethiopian famine in the 1980s, the protest marches over the genocide in Darfur in the early 2000s or even the #BringBackOurGirls campaign linked to the abduction of 276 schoolgirls from the Nigerian town of Chibok 10 years ago.

That lack of popular attention has translated into a dearth of political action to resolve wars in Africa or alleviate the suffering. (…)

The U.S. remains the leading funder of humanitarian aid in Africa despite the distractions in Europe and the Middle East. Washington contributed 47% to the U.N.’s Sudan emergency response plan in 2024 and nearly 70% of that for Congo.

Other traditionally large donors, including Germany and the U.K., have already cut their aid budgets amid the crisis in Ukraine and economic problems at home. And many experts expect substantial changes to U.S. foreign and aid policy under the incoming Trump administration, especially toward U.N. agencies—and a further waning of American influence.

The U.S. and the U.N. “were able to hold a line about what would be considered beyond acceptable for some cases,” says Acled’s Raleigh. “With the Trump administration coming in, that line will disappear. And so the self-interested conflicts that we’re seeing and the people creating violence across the continent will not be checked.”

The Economist, 12 janvier, article payant

Free markets : The capitalist revolution Africa needs

The world’s poorest continent should embrace its least fashionable idea

Extraits :

In the coming years Africa will become more important than at any time in the modern era. Over the next decade its share of the world’s population is expected to reach 21%, up from 13% in 2000, 9% in 1950 and 11% in 1800. As the rest of the world ages, Africa will become a crucial source of labour: more than half the young people entering the global workforce in 2030 will be African.

This is a great opportunity for the poorest continent. But if its 54 countries are to seize it, they will have to do something exceptional: break with their own past and with the dismal statist orthodoxy that now grips much of the world. Africa’s leaders will have to embrace business, growth and free markets. They will need to unleash a capitalist revolution.

If you follow Africa from afar you will be aware of some of its troubles, such as the devastating civil war in Sudan; and some of its bright spots, such as the global hunger for Afrobeats—streams on Spotify rose by 34% in 2024. Less easy to make out is the shocking economic reality documented in our special report this week and which we call the “Africa gap”.

In the past decade, as America, Europe and Asia have been transformed by technology and politics, Africa has, largely unnoticed, slipped further behind. Income per person has fallen from a third of that in the rest of the world in 2000 to a quarter. Output per head may be no higher in 2026 than it was in 2015. Two giants, Nigeria and South Africa, have done atrociously. Only a few countries, such as Ivory Coast and Rwanda, have bucked the trend. (…)

What should Africa’s leaders do? A starting-point is to ditch decades of bad ideas. These range from mimicking the worst of Chinese state capitalism, whose shortcomings are on full display, to defeatism over the future of manufacturing in the age of automation, to copying and pasting proposals by World Bank technocrats. The earnest advice of American billionaires on micro-policies, from deploying mosquito nets to designing solar panels, is welcome but no substitute for creating the conditions that would allow African businesses to thrive and expand. There is a dangerous strand of development thinking that suggests growth cannot alleviate poverty or does not matter at all, so long as there are efforts to curb disease, feed children and mitigate extreme weather. In fact in almost all circumstances faster growth is the best way to cut poverty and ensure that countries have the resources to deal with climate change.

So African leaders should get serious about growth. They should embrace the self-confident spirit of modernisation seen in East Asia in the 20th century, and today in India and elsewhere. A few African countries such as Botswana, Ethiopia and Mauritius have at different times struck what Stefan Dercon, a scholar, calls “development bargains”: a tacit pact among the elite that politics is about increasing the size of the economy, not just a fight to divvy up who gets what. More of those elite deals are needed.

At the same time governments should build a political consensus in favour of growth. The good news is that powerful constituencies are keen on economic dynamism. A new generation of Africans, born several decades after independence, care a lot more about their careers than they do about colonialism.

Narrowing the Africa gap calls for new social attitudes towards business, similar to those that unleashed growth in China and India. Instead of fetishising government jobs or small enterprises, Africans could do with more risk-taking tycoons. Individual countries need much more infrastructure, from ports to power, more free-wheeling competition and vastly better schools.

Another essential task is to integrate African markets so that firms can achieve greater economies of scale and attain an absolute size big enough to attract global investors. That means advancing plans for visa-free travel areas, integrating capital markets, plugging together data networks and finally realising the dream of a pan-African free-trade area.

The consequences for Africa of simply carrying on as usual would be dire. If the Africa gap gets bigger, Africans will make up nearly all of the world’s very poor, including the most vulnerable to climate change. That would be a moral disaster. It would also, through migration flows and political volatility, threaten the stability of the rest of the world.

But there is no reason to catastrophise or give up hope. If other continents can prosper, so can Africa. It is time its leaders discovered a sense of ambition and optimism. Africa does not require saving. It needs less paternalism, complacency and corruption—and more capitalism. ■

https://www.economist.com/leaders/2025/01/09/the-capitalist-revolution-africa-needs

L’Express, 29 novembre, libre accès

Sahel : au Tchad comme au Sénégal, l’armée française n’est plus la bienvenue

Afrique. Le Tchad a annoncé jeudi soir rompre ses accords de défense avec Paris. Même décision au Sénégal, où le président a informé de la fermeture à venir des bases françaises.

The Guardian, 29 novembre, libre accès

Swedish PM says Baltic sea now ‘high risk’ after suspected cable sabotage

Regional leaders meet after undersea telecoms cables severed, while Chinese ship remains at anchor nearby

The Guardian, 24 décembre, libre accès

UAE becomes Africa’s biggest investor amid rights concerns

Activists alarmed at emirati companies’ poor record on labour rights and fear projects may fail to address environmental concerns

Extraits:

The United Arab Emirates has become the largest backer of new business projects in Africa, raising hopes of a rush of much-needed money for green energy, but also concerns that the investments could compromise the rights of workers and environmental protections.

Between 2019 and 2023, Emirati companies announced $110bn (£88bn) of projects, $72bn of them in renewable energy, according to FT Locations, a data company owned by the Financial Times.

The pledges were more than double the value of those made by companies from the UK, France or China, which pulled back from big-ticket infrastructure investment projects in Africa after many failed to deliver expected returns. African leaders were also disappointed with climate finance pledges by western governments. At the Cop29 climate conference, for example, wealthy countries promised $300bn annually, whereas developing countries had demanded $1.3 tn.

Although African leaders have welcomed the increased interest from the Emiratis, some activists and analysts have expressed fears that the UAE’s poor record on labour rights for migrant workers, continued support for hydrocarbons and failure to address environmental issues will characterise its investments in Africa.

“African countries are in dire need of this money [for] their own energy transitions. And they plug huge holes, the Emirati investors, that the west failed to,” said Ahmed Aboudouh, an associate fellow at the Chatham House thinktank. “But at the same time they come in with less attention to labour rights, to environmental standards.” (…)

“African countries need all the financing and trade they can get,” said Ken Opalo, an associate professor at Georgetown University. “However, there is also the opportunity for the attention to breed criminality – like we are seeing in the gold sector.”